Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream | reviews, news & interviews

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

It’s unusual to leave an exhibition liking an artist’s work less than when you went in, but Tate Britain’s retrospective of Edward Burra manages to achieve just this. I’ve always loved Burra’s limpid late landscapes. Layers of filmy watercolour create sweeping vistas of rolling hills and valleys whose suggestive curves create a sexual frisson.

Take Valley and River, Northumberland 1972 (pictured below right), for instance. A spring emerges from a fold in green hills that resemble limbs. The landscape doubles as a body, with an inviting recess nestling between parted thighs.

These pastoral delights come as a blessed relief after the raucous and often ugly scenes filling the previous rooms. Burra began painting them when the rheumatoid arthritis he suffered from all his life became seriously debilitating. No longer able to nip over to France, Spain or New York for inspiration, he drove round Britain with his sister and, gazing at the view from her car, would store up images to turn into pictures on his return to Rye where he lived with his upper-class parents.

These pastoral delights come as a blessed relief after the raucous and often ugly scenes filling the previous rooms. Burra began painting them when the rheumatoid arthritis he suffered from all his life became seriously debilitating. No longer able to nip over to France, Spain or New York for inspiration, he drove round Britain with his sister and, gazing at the view from her car, would store up images to turn into pictures on his return to Rye where he lived with his upper-class parents.

It must have been a pretty dysfunctional family, since his excursions abroad often went unnoticed. Reduced by his debilitating illness to the role of voyeur, Burra was attracted to the seamy side of life. Escaping from Rye to the bars, clubs, dance halls and cabarets of Paris in the 1920s, he was excited by the sailors, prostitutes and other marginal figures frequenting these dives in circumstances so removed from the sleepy Sussex town where he lived.

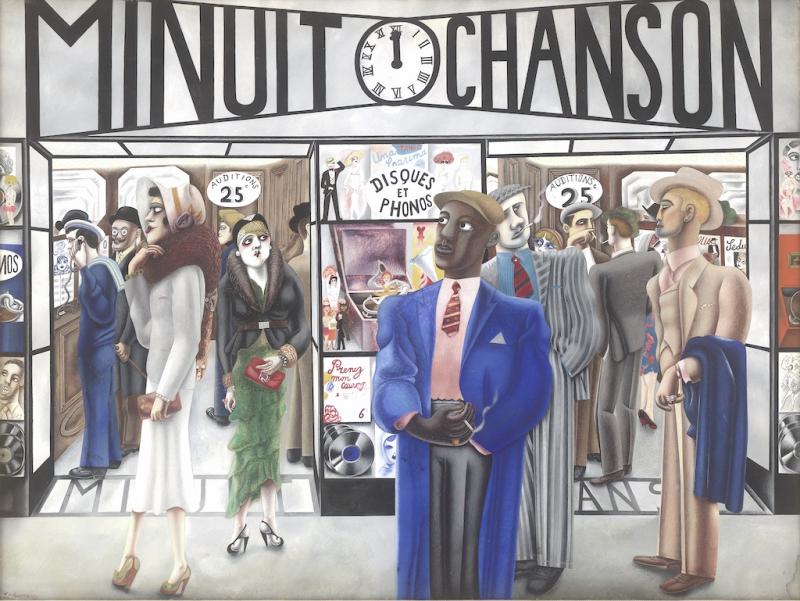

The crowded pictures he made on his return (main picture) are like stage sets peopled by exotic caricatures – black dudes posing in sharp suits, drunken sailors ogling the talent and women with exaggerated make-up wearing slinky gowns, fox furs and turbans.

I’ve always thought of these large-scale watercolours as social satire generated by a mix of sexual excitement and admiration, but seeing so many of them together reveals a nastier streak. There’s humour all right, but it feels mean spirited. Burra’s pleasure-seeking dames and dudes are on the make – callous and predatory – and his sharply critical eye suggests that he viewed them as low life.

I’ve always thought of these large-scale watercolours as social satire generated by a mix of sexual excitement and admiration, but seeing so many of them together reveals a nastier streak. There’s humour all right, but it feels mean spirited. Burra’s pleasure-seeking dames and dudes are on the make – callous and predatory – and his sharply critical eye suggests that he viewed them as low life.

Hogarth is cited as an influence, but Otto Dix seems more likely as a source of inspiration. With their harsh make-up and self-regarding stylishness, the two women in Balcony Toulon 1929 (pictured above) are like sisters to Sylvia von Harden, the journalist portrayed by Dix in his clever but cruel portrait of 1926.

And Burra’s John Deth (Hommage to Conrad Aiken) 1931 (pictured below) could be mistaken for one of Dix’s scenes of wartime decadence, in which everyone has lost their moral compass. It’s party time and the womb-like interior of a nightclub is peopled by revellers indulging in orgies of eating, drinking and fornicating in an attempt to escape thoughts of death. But among the guests is the Grim Reaper embracing a woman in a green party frock and ridiculous plumed hat.

Dix’s anger arose from his experiences as a gunner on the Western front in World War I. Holding politicians, bankers and businessmen responsible for the carnage, he portrayed them as corrupt and contemptible. Burra had no such reason to hate, yet he said: “The very sight of people’s faces sickens me. I’ve got no pity… I get such paroxysms of impotent venom, I feel it must poison the atmosphere.”

One gallery is devoted to the sets and costumes he designed for choreographers Frederick Ashton and Ninette de Valois and productions at Sadler’s Wells and the Royal Opera House and, boy, was he in his element. The theatricality that often makes his paintings feel too staged now makes perfect sense. Burra was a jazz enthusiast, and excerpts from his collection play in one gallery – as though the visual clamour of his overcrowded pictures was not noise enough. In this room, music from the various productions he worked on provides another annoying soundtrack. It’s a huge relief, then, to reach the last room where you can enjoy, in silence, those blissfully calm and empty landscapes which are imbued with much gentler, less acerbic humour.

It’s a huge relief, then, to reach the last room where you can enjoy, in silence, those blissfully calm and empty landscapes which are imbued with much gentler, less acerbic humour.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment