Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal | reviews, news & interviews

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt studied at Goldsmiths College at the same time as YBAs (Young British Artists) like Damien Hirst and Gillian Wearing; but whereas they would become household names so their work is now familiar, he disappeared from view. It makes his Whitechapel retrospective feel like a rediscovery – incredibly fresh and immediate.

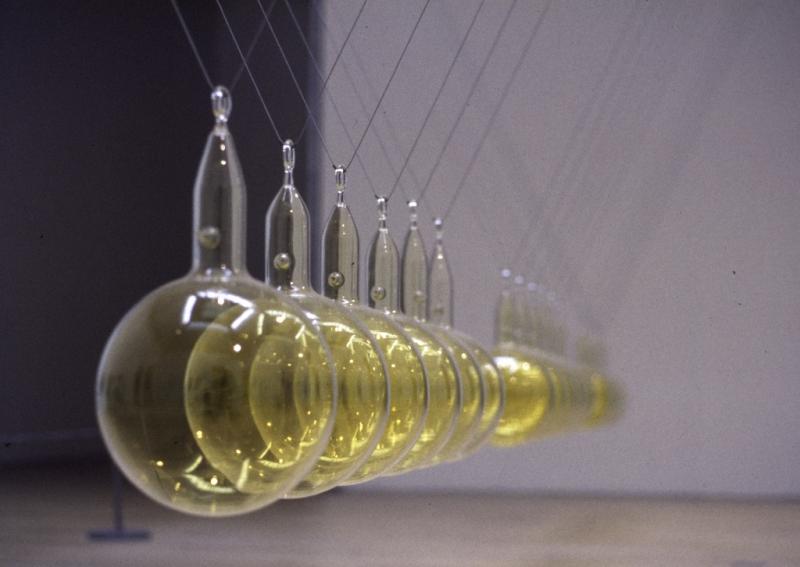

Stepping into the main gallery, you are infused with a supreme sense of calm. Hanging from the ceiling is a Newton’s cradle – 18 glass orbs suspended a few inches apart on fine wires (main picture). Glowing golden yellow, these fragile vessels are serenely beautiful.

Knock into one, though, and it would smash into its neighbour and release the contents – mustard gas – the toxic substance that injured my grandfather and blinded or killed thousands more during World War One.

Accompanying this Cradle are two equally dangerous sculptures. Three metal arcs form an arch; their tips are glass vials filled with bromine, a carcinogen that also burns the skin. Nearby, a steel ladder rests against the wall. The rungs (pictured right) are glass capsules filled with iodine crystals and an electric current ascends the steps, one by one, heating up the crystals and transforming them into a poisonous vapour.

Accompanying this Cradle are two equally dangerous sculptures. Three metal arcs form an arch; their tips are glass vials filled with bromine, a carcinogen that also burns the skin. Nearby, a steel ladder rests against the wall. The rungs (pictured right) are glass capsules filled with iodine crystals and an electric current ascends the steps, one by one, heating up the crystals and transforming them into a poisonous vapour.

The installation was first shown in 1994 at the Milch Gallery without any protective barriers, so the danger it presented was real. During a crowded private view, for instance, a glass vessel could easily have been broken. And when it was shown at the Tate the following year, iodine fumes leaked from the ladder. The incident made its way onto Sky news – you can watch a clip in the archive gallery – and prompted a cartoon in the Evening Standard of a guy selling gas masks to unwary gallery goers.

At the Whitechapel, the sculptures are surrounded by perspex boxes that reduce the risk to the point where it becomes little more than an idea. Rather than diminishing the impact, as you might expect though, the transformation from an actual to a metaphorical hazard serves only to enhance the work’s potency. By focusing attention on the sublime beauty of the fragile vessels, it makes their toxic potential seem even more treacherous and unexpected. Butt had good reason to fear the presence of invisible toxins and lethal pathogens. He was queer at a time when the AIDS virus had begun to decimate the gay community. And not long after his partner died of AIDs, the artist also succumbed to an AIDs related illness. He was only 32; it was 1994 and he and his fellow alumni were just beginning to gain recognition.

Butt had good reason to fear the presence of invisible toxins and lethal pathogens. He was queer at a time when the AIDS virus had begun to decimate the gay community. And not long after his partner died of AIDs, the artist also succumbed to an AIDs related illness. He was only 32; it was 1994 and he and his fellow alumni were just beginning to gain recognition.

Butt was born in Pakistan and brought to London at the age of two. As a gay Muslim he always felt like an outsider, excluded from British society by dint of his colour, faith and sexuality at a time when racism and homophobia were rampant. And his degree show featured Transmission, a work whose title refers to the dissemination of blind faith and prejudice, as well as to the spread of disease.

Resting on rehals (Quran stands) are nine books (pictured above) whose glass pages are delicately engraved with a triffid, the man-eating plant that runs amok in John Wyndham’s 1951 sci-fi classic The Day of the Triffids. Butt has subtly modified the plant that appears on the cover of the original paperback so that its soft body reminds one of a testicle sack and its long neck a penis ejaculating a spurt of lethal droplets. The books are lit by ultra violet light that, without the protective goggles provided, could seriously damage your eyesight – blinding you (with bigotry).

Resting on rehals (Quran stands) are nine books (pictured above) whose glass pages are delicately engraved with a triffid, the man-eating plant that runs amok in John Wyndham’s 1951 sci-fi classic The Day of the Triffids. Butt has subtly modified the plant that appears on the cover of the original paperback so that its soft body reminds one of a testicle sack and its long neck a penis ejaculating a spurt of lethal droplets. The books are lit by ultra violet light that, without the protective goggles provided, could seriously damage your eyesight – blinding you (with bigotry).

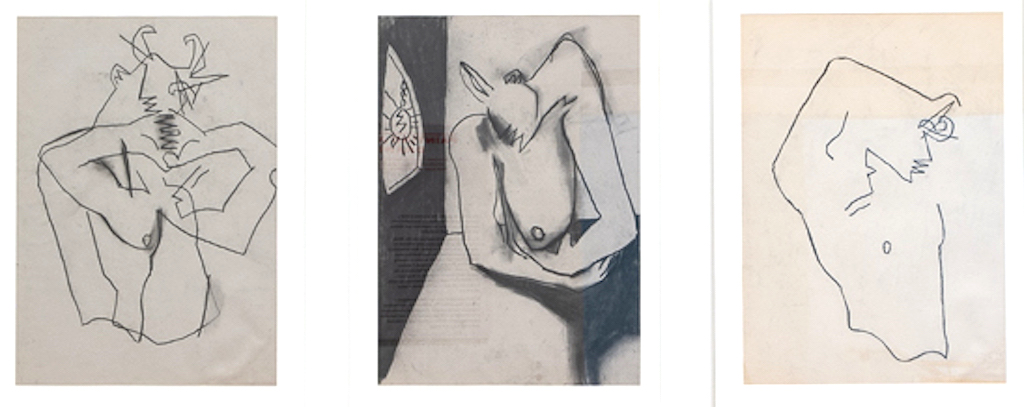

The triffid also appears on video in an animated sequence (pictured above left) of drawings coloured in pastel shades that belie the danger of contagion which the plant came to symbolise. Also on show are early line drawings (pictured below) and etchings, mainly of male nudes, that reveal another side of the conceptual artist – as an accomplished draughtsman.

And a series of exquisite pastel drawings feature the triffid walking abroad. The deadly plant follows a hyphenated line, described by the artists as a “line of intent”, as though following a chart or pursuing a predetermined path whose goal is the unrelenting destruction of homo sapiens.

And a series of exquisite pastel drawings feature the triffid walking abroad. The deadly plant follows a hyphenated line, described by the artists as a “line of intent”, as though following a chart or pursuing a predetermined path whose goal is the unrelenting destruction of homo sapiens.

Given the artist’s untimely death, the broken lines also feel like a premonition, an unwelcome prefiguring of the fact that his career is stuttering to a premature halt. Before becoming ill himself, Butt stopped working in order to nurse his ailing partner. The irony is that this brutal disruption lends the work even more potency by ensuring that it remains always fresh, immediate and heart felt.

- Hamad Butt: Apprehensions is at the Whitechapel Gallery until 7 September

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Comments

I was lucky to catch this

I was lucky to catch this exhibition at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) in Dublin. Thanks for further enlightenment, and I'll go and see it again.