Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness | reviews, news & interviews

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

This must be the first time a black artist has been honoured with a retrospective that fills the main galleries of the Royal Academy. Celebrating Kerry James Marshall’s 70th birthday, The Histories occupies these grand rooms with such joyous ease and aplomb that it makes one forget how rare it is for blackness to be given centre stage.

“I’m trying to establish a phenomenal presence that is unequivocally black and beautiful,” explains Marshall. “What I’m trying to do in my work is establish presence with a capital P.” And boy does he succeed! Gallery after gallery is filled with pictures that unapologetically embed black people within the canon.

In the first room hangs a picture of a black painter. It’s an emphatic declaration of the right to be an artist – to look, to paint and be acknowledged. He has the chiselled features of an ebony wood carving and stares us down through eyes resembling ivory inlays or the white painted orbs of a Congolese power figure (nkisi nkondi), whose role is to give protection against malevolent forces.

In the first room hangs a picture of a black painter. It’s an emphatic declaration of the right to be an artist – to look, to paint and be acknowledged. He has the chiselled features of an ebony wood carving and stares us down through eyes resembling ivory inlays or the white painted orbs of a Congolese power figure (nkisi nkondi), whose role is to give protection against malevolent forces.

The painting is a tour de force. The wood panelling behind the artist resembles a monochrome Mondrian while, splattered with blobs and squiggles of paint, his palette has grown so enormous that it reads as an abstract painting. By positioning himself – literally and metaphorically – between geometric and expressive abstraction, he is asserting his command of both languages while demonstrating his mastery of figure painting.

It’s a deliberate provocation. When in the late 1970s, Marshall was a student at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles, conceptualism was the order of the day; and since painting, in general, and figurative panting, in particular, were considered old hat, he was out of step in every way. The picture is an act of defiance, then, a demonstration of his determination to paint, no matter what the opposition.

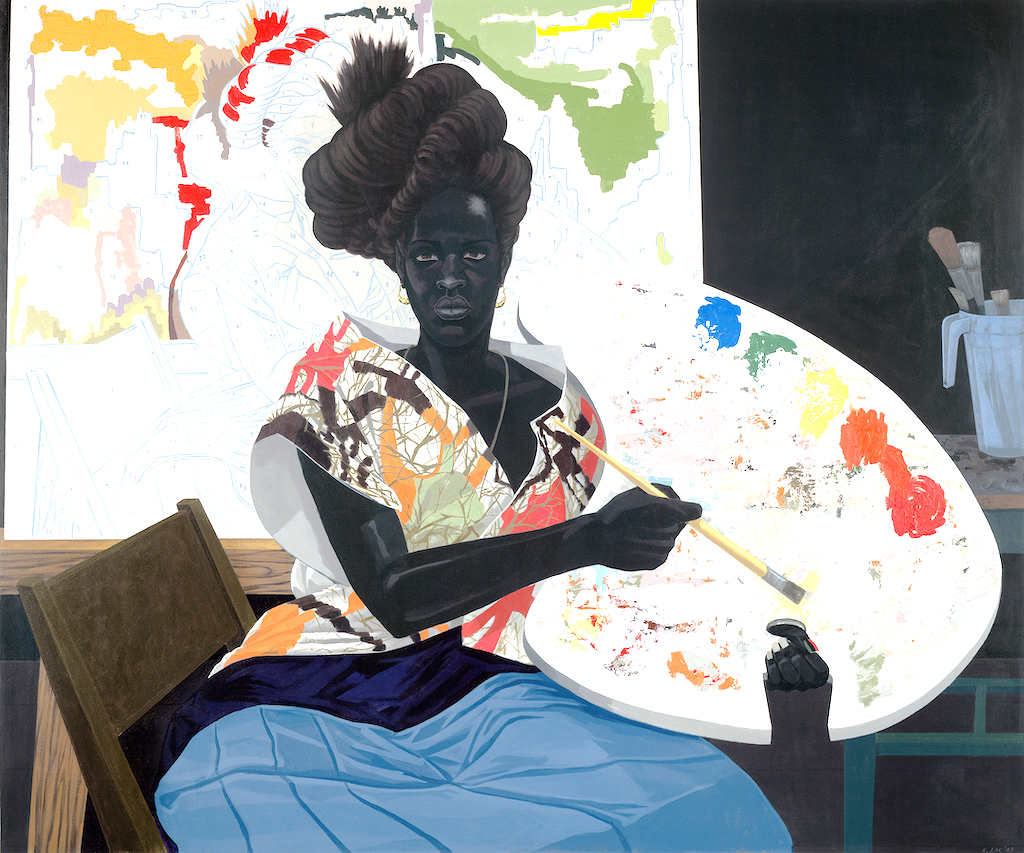

This painter has a supremely stylish sister (pictured above right). Dressed in a blouse resembling a modernist design and sporting a dramatic topknot, she reminds me of Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun’s 1782 portrait of herself in a flamboyant straw hat. Both women gaze confidently at the viewer while holding a brush and palette indicative of their trade; but Marshall’s picture contains further layers of meaning. On an easel behind the artist is a painting-by-numbers version of her portrait that includes a second easel, on which is a partially filled-in abstraction.

Again and again, Marshall creates layers like this of abstract and figurative elements which alongside exquisite detail indicate the complexities of a story –whether it be kids playing in a park, a couple hanging out on a balcony, a busy beauty salon or bounty hunters kidnapping children.

Knowledge and Wonder (pictured below) is a case in point. Painted in 1995 for the Chicago Public Library, this huge canvas features a group of children gazing at three giant books whose cover designs explode into the room with the combined energy of galaxies and shooting stars, strong men and tribal masks. The excitement is palpable; never before has a row of backs looked so expressive, and never before has the acquisition of knowledge been made to seem so stimulating and so empowering. It even propels a black kid into the future on what looks like a flying saucer.

Knowledge and Wonder (pictured below) is a case in point. Painted in 1995 for the Chicago Public Library, this huge canvas features a group of children gazing at three giant books whose cover designs explode into the room with the combined energy of galaxies and shooting stars, strong men and tribal masks. The excitement is palpable; never before has a row of backs looked so expressive, and never before has the acquisition of knowledge been made to seem so stimulating and so empowering. It even propels a black kid into the future on what looks like a flying saucer.

My favourite picture is School of Beauty, School of Culture, 2012 (main picture), a salon where stylish women gather to perfect their make-up and elaborate hairdos. Even in a place dedicated to black beauty, there’s an issue, though. Two toddlers have noticed a strange shape hovering in the foreground. Inspired by the anamorphic skull in Holbein's The Ambassadors 1533, this apparition is of a blonde cutie whose looks supposedly represent an ideal against which these women may well be judged and found wanting. Her image hovers in the air like a bad smell.

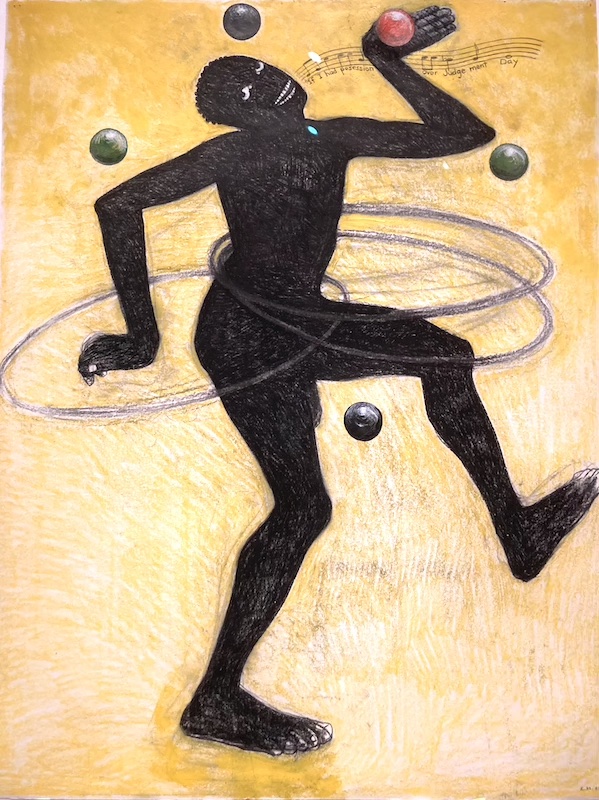

Before embarking on paintings like these which unequivocally put black people in the frame, Marshall first addressed their absence from the art of the past. Inspired by Ralph Ellison’s novel Invisible Man whose protagonist feels invisible because he is unwelcome in society, the artist depicts a black man on a black panel, invisible save for his teeth and the whites of his eyes. Look more closely, though, and the figure comes into view – but as a dancing, singing “coon” rather than an individual. The only choice on offer was between invisibility and a demeaning racial stereotype (pictured above left).

Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of his Former Self 1980, presents Marshall in the guise of another stereotype. Wearing a black coat and fedora, he is little more than a grinning spectre lurking in the shadows, clownish yet menacing. There he is again, hanging on the wall of a room empty save for an old-fashioned vacuum cleaner – a wry comment on the role of servant or menial traditionally occupied by black people in paintings.

Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of his Former Self 1980, presents Marshall in the guise of another stereotype. Wearing a black coat and fedora, he is little more than a grinning spectre lurking in the shadows, clownish yet menacing. There he is again, hanging on the wall of a room empty save for an old-fashioned vacuum cleaner – a wry comment on the role of servant or menial traditionally occupied by black people in paintings.

Marshall helps to fill this void by making imaginary portraits of overlooked historical figures such as the poet Phillis Wheatley-Peters, the painter Scipio Moorhead and Harriett Tubman who, having escaped slavery herself, set up an “Underground Railway” of safe houses that helped countless others make a getaway.

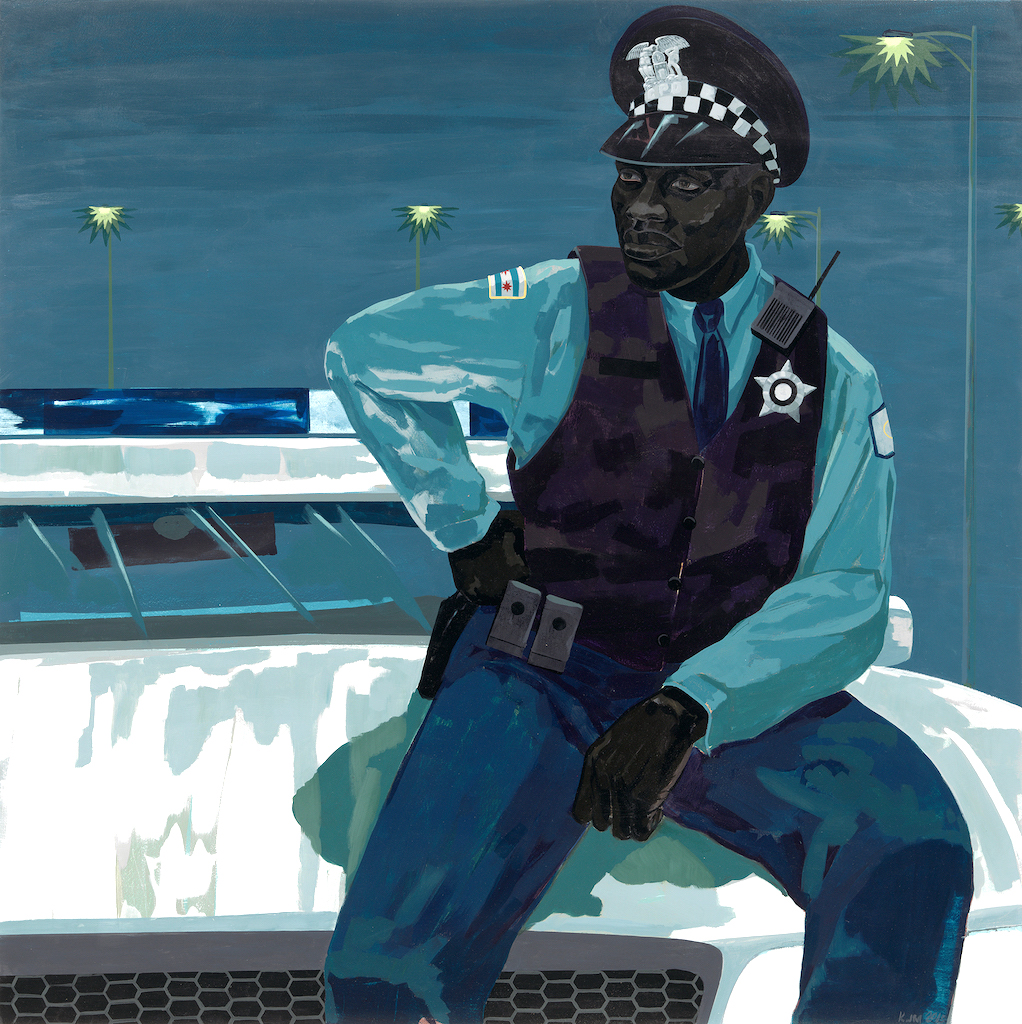

Not all his characters are good guys, though. In the woods and on the beaches, bounty hunters can be seen kidnapping fellow Africans to sell into slavery. More ambiguous is a mean-looking cop perched on the bonnet of a patrol car (pictured above right). Is he keeping his community safe, or has he sold his soul to the white establishment?

Nat Turner is a deliberately contentious figure. The leader of an 1831 slave uprising, there he stands, axe in hand, in front of a bed on which lies the severed head of his master. Referring back to one of Artemisia Gentileschi’s favourite subjects – the Old Testament story of Judith slaying Holofernes – Marshall invites us to decide if Turner is to be revered as a hero or reviled as a villain. “I’ve always wanted to be a history painter on a grand scale”, says Marshall. But his paintings have little in common with the tedious celebrations of victories and conquests that come to mind. They may be as ambitious in scope, but they are far more intelligent, far more nuanced and much more fun. That’s how you make your way into the citadel (of high art) and unapologetically take it by storm.

“I’ve always wanted to be a history painter on a grand scale”, says Marshall. But his paintings have little in common with the tedious celebrations of victories and conquests that come to mind. They may be as ambitious in scope, but they are far more intelligent, far more nuanced and much more fun. That’s how you make your way into the citadel (of high art) and unapologetically take it by storm.

- Kerry James Marshall: The Histories at the Royal Academy until 18 January 2026

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Add comment