Robert Redford: remembering All the President’s Men | reviews, news & interviews

Robert Redford: remembering All the President’s Men

Robert Redford: remembering All the President’s Men

The iconic filmmaker, who died this week, reflecting on one of his most famous films

In the summer of 2005, Robert Redford, who died this week, attended the Karlovy Vary Film Festival in the Czech Republic, to collect a life achievement award. And his appearance in front of the media coincided with a startling news story that was rippling around the world.

Just a week before, Mark Felt, a former deputy director of the FBI, admitted that he was the mysterious Deep Throat – the anonymous source who, in the 1970s, had offered Washington Post reporters information about Watergate, the conspiracy that would lead to the fall of President Richard Nixon.

This story is the subject of one of Redford’s most lauded films, the political thriller All the President’s Men (1976), directed by Alan Pakula and co-starring Redford and Dustin Hoffman as the reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. So here was a perfect opportunity for Redford to reflect on the film, which he was instrumental in getting made, as well as the role of the media both in the Seventies and in 2005, as the US was embroiled in another controversial presidency, that of George W Bush. And this most intelligent, articulate and politically engaged of filmmakers didn't hold back. (Pictured below, left to right: Redford, Jack Warden, Hoffman and Jason Robards as Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee.)

Karlovy Vary, July 2005

WITH the outing of FBI man Mark Felt as the infamous “Deep Throat” of the Watergate scandal, the film charting the journalistic exposure of that story, All the Presidents Men, has once more been in everyone’s minds – not least the images of Robert Redford, as Bob Woodward, lurking in menacing underground car parks waiting for the man who would urge him to “follow the money”.

Redford, one of the most political, and liberal of American actors, has welcomed the attention paid one of his best films. “It’s 30 years old, but has taken on a new relevance right now in terms of the state of the media and politics in America,” he says. “It’s kind of interesting, because a lot of people now, who were not even born then, are seeing it as new. That’s very exciting.”

What’s exciting to me, apart from finding Redford thousands of miles from home in the Czech Republic, where he has come to collect an award for his contribution to world cinema at the Karlovy Vary Film Festival, is the story he tells about his own involvement in President’s Men – pursuing Woodward and Bernstein, with a desire to film their story, long before their scoop was to bring down Richard Nixon.

“I was making The Way We Were in 1972 and following Watergate in the newspapers,” he recalls. “And in July and August there were these small articles that began to appear with these two names on them, Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward. They were talking about this slush fund for the committee to re-elect the president, and they started naming people and the stories were getting bigger and bigger, and as that happened I got really excited. Then the Nixon administration completely turned on the Washington Post, accusing them of bias, lying, scurrilously, unpatriotic reporting – very similar things to what are happening now.

“Then I read a story about who these guys Woodward and Bernstein were: one guy was a Jew, the other was a Wasp, one guy was a radical liberal the other a Republican. They didn’t like each other but they had to work together. I thought that’s a pretty good character study, maybe it will make a nice little movie.”

He got on the telephone and – something perhaps Hollywood stars, even as defiant a non-celebrity as Redford, would not be accustomed to – neither Woodward nor Bernstein would take his calls. Thus started a long campaign by the actor to get the reporters’ attention, all the while getting on with the life of making movies – he had completed The Way We Were, The Sting and The Great Gatsby by the time he finally got their attention.

“I didn’t realise of course that they were very frightened. They were under surveillance, they didn’t trust anyone and they didn’t think it was me, they thought it was a set-up.” When Woodward did agree to meet, it was at a secret location in Washington. Redford, who is still friends with the reporter, chuckles at the memory. “Even that was kinda like Deep Throat.” (Pictured left: Hal Holbrook as Deep Throat in the film.)

“I didn’t realise of course that they were very frightened. They were under surveillance, they didn’t trust anyone and they didn’t think it was me, they thought it was a set-up.” When Woodward did agree to meet, it was at a secret location in Washington. Redford, who is still friends with the reporter, chuckles at the memory. “Even that was kinda like Deep Throat.” (Pictured left: Hal Holbrook as Deep Throat in the film.)

He might be 68, but Redford is still sharp as a button – sartorially and mentally. Dressed in blue jeans, crisp white shirt and baseball cap, he looks as though he’s just stepped off the ranch. And when the cap’s removed the famous mop of blond hair looks as lustrous as it did when he made his name opposite Paul Newman in the best buddy movie of all time, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

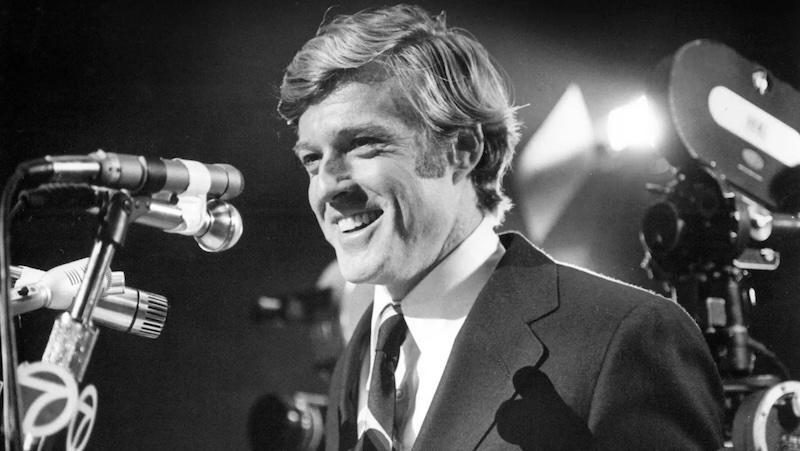

It’s too easy to forget what a significant star Robert Redford is. In his heyday in the Seventies, with films as diverse as Butch Cassidy, The Way We Were, Tell Them Willy Boy is Here, Three Days of the Condor and The Candidate (another brilliant political film, this time a stinging satire of the campaign process) he was regularly the number one box office draw; but unlike, say, Tom Cruise, who achieves this with one popcorn blockbuster after another, Redford did it with issues-based films that reflected the political and cultural issues of the day. He may have been a pin-up, but the boy had brains and a conscience to boot. (Pictured below, Redford in The Candidate.)  Since then he’s established himself as a competent director (unlucky, in a way, that his best film and director Oscars for Ordinary People will only be remembered for depriving Scorsese and Raging Bull), while using his wealth, contacts and prestige to turn the Sundance Film Festival into the ever-present guardian of independent cinema.

Since then he’s established himself as a competent director (unlucky, in a way, that his best film and director Oscars for Ordinary People will only be remembered for depriving Scorsese and Raging Bull), while using his wealth, contacts and prestige to turn the Sundance Film Festival into the ever-present guardian of independent cinema.

It’s funny. No-one watching the two impossibly handsome men gallivanting around Butch Cassidy would have imagined them both becoming such sterling ambassadors for the film star breed. But Newman has made millions for charity from his homemade sauces, while the non-profit Sundance Institute and festival – which have directly benefited or championed the likes of the Coen brothers, Steven Soderbergh Todd Haynes and Quentin Tarantino – has helped keep American cinema sliding headlong into terminal banality.

The precision of Redford’s recollections and the anger of his political views make for compulsive listening. He says that he values All the President’s Men because it was made when journalism was at a high point. “The role those journalists played in saving our first amendment – freedom, basically – was a wonderful thing. Now 30 years later I’m watching very similar patterns emerge in American politics: stonewalling, not telling the truth, putting people under wire taps and surveillance. But where is the press now? Where is the press?”

In lieu of journalists who seem to have spent five years running away from the story, I wonder whether cinema can do something to address the political situation, or at least reflect it?

“With All the President’s Men we spent a lot of time on detail, and it’s a film about the power of detail, and focus and attention and relentless pursuit. I don’t think a film like that is possible today. I think the attention span is different, I think young people are more interested in quick, easy entertainment, and the business has changed, it is all about marketing and following the youth market with new technology, special effects; so many movies are more like cartoons. I’m sorry to say the medium is more celebrity orientated, more shallow.

“That’s why I started Sundance, to keep alive independent type movies, because those are the films that I like to make. I wanted to give opportunities for new artists to could come and develop their art, let them speak, let them tell their stories.”  Despite his enduring enthusiasm for Sundance, Redford admits that his own acting career has bottomed out to little more than a film a year, because of the dearth of the “more unique, independent, darker more reality based films” he himself is interested in.

Despite his enduring enthusiasm for Sundance, Redford admits that his own acting career has bottomed out to little more than a film a year, because of the dearth of the “more unique, independent, darker more reality based films” he himself is interested in.

That fact, he insists, has not extinguished his love of acting. Indeed, later this year he has a starring role, as Jennifer Lopez’s father-in-law no less, in Lasse Hallstrom’s An Unfinished Life.

There’s a sense, though, that Redford is putting more of his efforts into his political campaigning work, especially on the environment, and galvanised by his very public distaste for George W Bush.

His appearance in Karlovy Vary, a charming festival with an emphasis on eastern European cinema – and where he has just met another crusading artist, Vaclav Havel – has meant a lot to Redford.

“When I was a young man, starting out, I was an artist,” he recalls. “I was 18 and I wanted to leave my country and experience the world. I felt that I would receive a better education that way. So I came to Europe with very little money, I had to learn languages, I travelled as we say in America ‘on the bum’. And my experience living in Europe for a year and a half had a great impact on me, because it created my world view, it shaped how I would see the world and how I would see my own country.

“That included appreciating what was good about my country, that it had these freedoms – freedom of speech, freedom of dissent, freedom of expression. As I travelled I could see that not every country had that. I couldn’t even get into Prague at that time, for example; and as the Hungarian revolution was going on I assisted as a volunteer to help bring refugees across the Danube.

“So when I came back to the United States and went into film, I carried that experience with me. I’m very proud of my country, but I’m not happy with the way things are now; it’s no secret that I disagree with this administration and most of its policies and I will continue to fight in whatever way I can against those policies, whether it’s the environment, or education, or human rights.”

Whatever he does politically, Redford prefers to work “behind the scenes,” he says. “The main thing I do, as an artist, is direct, act in and produce films. And that’s what I hope to continue to do. Unless, of course, the film business gets so impossible that I can’t.”

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Little Trouble Girls review - masterful debut breathes new life into a girl's sexual awakening

Urska Dukic's study of a confused Catholic teenager is exquisitely realised

Little Trouble Girls review - masterful debut breathes new life into a girl's sexual awakening

Urska Dukic's study of a confused Catholic teenager is exquisitely realised

Young Mothers review - the Dardennes explore teenage motherhood in compelling drama

Life after birth: five young mothers in Liège struggle to provide for their babies

Young Mothers review - the Dardennes explore teenage motherhood in compelling drama

Life after birth: five young mothers in Liège struggle to provide for their babies

Add comment