Blu-ray: Darling | reviews, news & interviews

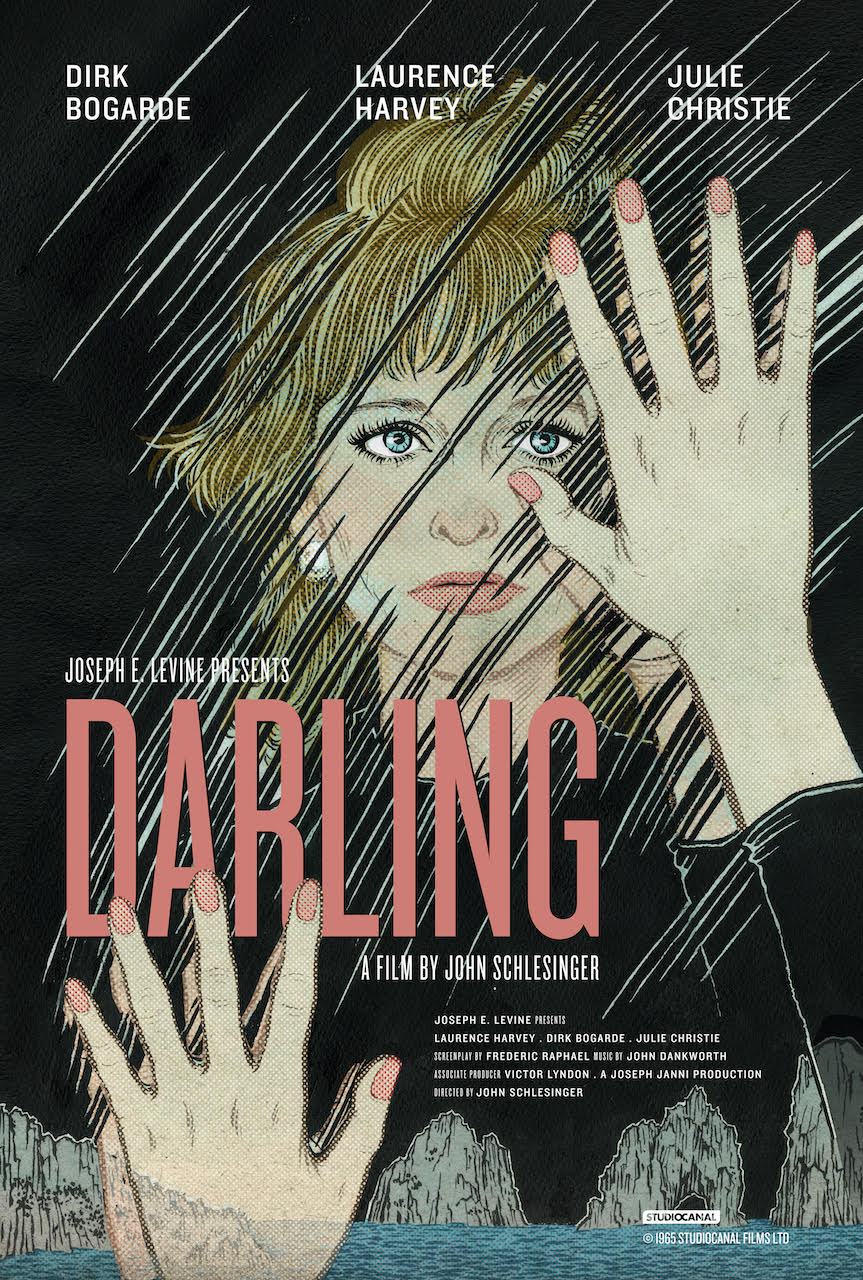

Blu-ray: Darling

Blu-ray: Darling

John Schlesinger's Sixties classic now feels problematic, but retains an icky fascination

A look at Darling on its 60th anniversary offers a sobering reality check on the "Swinging Sixties", a reminder of the fallacy of the decade’s gaiety and supposed liberation, especially for women.

This attractive 4K restoration reveals the film to be a very complicated animal indeed – both in its own time and through the prism of today’s very different political correctness and gender ethics. While John Schlesinger’s "classic" plays like a scathing satire of the period, I’m not convinced that this was entirely intentional at the time, which of course makes it even more interesting.

The film originated with Schlesinger and his long-time producer, Joseph Janni. Hot on the heels of back-to-back kitchen sink dramas, A Kind of Loving (1962) and Billy Liar (1963), there seems to have been a conscious desire to move away from social realism and the northern locales of those films to something more indicative of the flash and excitement that was taking place down South.

The film originated with Schlesinger and his long-time producer, Joseph Janni. Hot on the heels of back-to-back kitchen sink dramas, A Kind of Loving (1962) and Billy Liar (1963), there seems to have been a conscious desire to move away from social realism and the northern locales of those films to something more indicative of the flash and excitement that was taking place down South.

In his new interview for this disc, screenwriter Frederick Raphael puts it bluntly: “They were quite tired of the lower classes and the dialogue. They wanted to do something classier.”

For both director and star, a very tangible transition exists on screen, in the penultimate scene of Billy Liar, Julie Christie’s character looking out of the train window as it whisks her away from Bradford and towards a new life in London, leaving the timid Billy to mere daydreams of escape. The change of setting and style would consolidate Schlesinger’s reputation and make a star of Christie, who would win her only Oscar for the performance.

And according to a short audio interview with Schlesinger, on this disc, the germ of the idea came from the Billy Liar shoot, namely Godfrey Winn, the presenter of the radio show Housewives’ Choice that features at the start of the film. Winn, who was keen to write a script, related a real story of a syndicate of showbiz and businesspeople who had rented a flat for the "kept woman" they shared, who then committed suicide by jumping off a balcony.

Perhaps the tragedy of this story sat uncomfortably with Schlesinger’s intentions; perhaps it was just too close to the plot of Billy Wilder’s The Apartment (1960). Either way, with Raphael the script now featured the character of Diane Scott, someone with far more agency than The Apartment’s Fran Kubelik and – for that very reason, perhaps – is presented with far less sympathy by the male filmmakers.  Diane is a young woman with ambitions; her problem, primarily, is that she isn’t entirely sure what those ambitions are, changing her mind – career-wise and romantically – from one moment to the next. She’s a model, a would-be actress, a socialite, smart and adaptable enough to move between worlds, her beauty and good humour very effective calling cards. She starts the film married, then moves in with journalist Robert Gold (Dirk Bogarde), with whom she seems genuinely happy, until his stay-at-home nature and her need to move onward and upward draws her towards wealthy and amoral advertising executive Miles Brand (Laurence Harvey, pictured above with Christie.) Eventually, an Italian prince will draw her away from London altogether.

Diane is a young woman with ambitions; her problem, primarily, is that she isn’t entirely sure what those ambitions are, changing her mind – career-wise and romantically – from one moment to the next. She’s a model, a would-be actress, a socialite, smart and adaptable enough to move between worlds, her beauty and good humour very effective calling cards. She starts the film married, then moves in with journalist Robert Gold (Dirk Bogarde), with whom she seems genuinely happy, until his stay-at-home nature and her need to move onward and upward draws her towards wealthy and amoral advertising executive Miles Brand (Laurence Harvey, pictured above with Christie.) Eventually, an Italian prince will draw her away from London altogether.

Diane may be one of cinema’s first female anti-heroes, outside the very particular template of the femme fatale. She acts poorly, but Christie’s rich characterisation, full of spontaneity and charm, makes it impossible not to like her. Moreover, it's clear, ultimately, that the person she’s harming the most is herself.

At the same time, the film leaves an odd taste. On the one hand, it clearly manifests the appalling quality of the male-dominated worlds in which Diane is attempting to find her way; except for Gold and Malcolm (Roland Curram), a gay photographer who befriends her, the men – politicians, financiers, artists – are equally loathsome, the male gaze at its most abhorrent. On the other hand, the judgements rained down upon her, even by Gold, are disproportionately harsh – and would not be levied at a man.

This restored version comes with a pre-credits caution of “historical attitudes which some people may find insulting or offensive”. And the Blu-ray package pointedly features both the original trailer – loaded head to toe with acerbic swipes at Diane’s character – and the current one, in which these are entirely absent.

However socially aware Schlesinger, Raphael and Janni may have felt they were being, the fact that Christie was unhappy about the full nudity required of her, and persuaded nonetheless, speaks to their ethical inconsistency. One can make a narrative argument for that one nude scene, the clothes horse stripped bare of her camouflage at just the moment that she realises she's traded up a step too far. But there were other ways.

There’s an argument, too, that the filmmakers were doing their best, in the context of the period in which they were working – the film is quite bold and brazen for its time. And it conveys the Sixties well, whether through Gold’s work as a journalist (a sweet interview with a literary author; a vox pop with a homophobe made piquant by our knowledge of Bogarde’s own, closeted sexuality), Diane’s stunning wardrobe, or its depiction of what "swinging" meant for Parisians.  While the interviews with Schlesinger and Raphael aren’t revealing of anything other than a certain antipathy between the two men, fashionistas will find more value in an on-camera talk by Dr Josephine Botting on the work of the film’s designer Julie Harris, who won an Oscar along with Christie and Raphael; it is Botting who makes the astute observation that Diane is “more in control of her image than her emotions or desires”. A booklet includes an article on her designs, an appreciation of the director, and essays on “Darling’s insatiable anti-heroine”, “female ambition in the Swinging Sixties”, and the portrayal of the two men of the film, who contribute to one of cinema’s most distinctive love triangles.

While the interviews with Schlesinger and Raphael aren’t revealing of anything other than a certain antipathy between the two men, fashionistas will find more value in an on-camera talk by Dr Josephine Botting on the work of the film’s designer Julie Harris, who won an Oscar along with Christie and Raphael; it is Botting who makes the astute observation that Diane is “more in control of her image than her emotions or desires”. A booklet includes an article on her designs, an appreciation of the director, and essays on “Darling’s insatiable anti-heroine”, “female ambition in the Swinging Sixties”, and the portrayal of the two men of the film, who contribute to one of cinema’s most distinctive love triangles.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Little Trouble Girls review - masterful debut breathes new life into a girl's sexual awakening

Urska Dukic's study of a confused Catholic teenager is exquisitely realised

Little Trouble Girls review - masterful debut breathes new life into a girl's sexual awakening

Urska Dukic's study of a confused Catholic teenager is exquisitely realised

Young Mothers review - the Dardennes explore teenage motherhood in compelling drama

Life after birth: five young mothers in Liège struggle to provide for their babies

Young Mothers review - the Dardennes explore teenage motherhood in compelling drama

Life after birth: five young mothers in Liège struggle to provide for their babies

Blu-ray: Finis Terrae

Bleak but compelling semi-documentary, filmed on location in Brittany

Blu-ray: Finis Terrae

Bleak but compelling semi-documentary, filmed on location in Brittany

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Sex review - sexual identity slips, hurts and heals

A quietly visionary series concludes with two chimney sweeps' awkward sexual liberation

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Sex review - sexual identity slips, hurts and heals

A quietly visionary series concludes with two chimney sweeps' awkward sexual liberation

Add comment