Hallé, Elder, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - premiere of new Huw Watkins work | reviews, news & interviews

Hallé, Elder, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - premiere of new Huw Watkins work

Hallé, Elder, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - premiere of new Huw Watkins work

Craftsmanship and appeal in this 'Concerto for Orchestra' - and game-playing with genre

Huw Watkins’ Concerto for Orchestra, the fourth new work of his to be commissioned and premiered by the Hallé and Sir Mark Elder, is another beautifully crafted and highly appealing construction.

It’s also intriguing in its game-playing with genre, in almost a mirror image of the way his First Symphony was back in 2017. That, a two-movement piece, was undoubtedly symphonic by the time it reached its somewhat surprising ending, but managed to give the impression of being a concerto for orchestra at many points along the way.

This, in three movements and running for around 35 minutes in total, is undoubtedly what its title says but has some of the elements of traditional symphony structure embedded in it. In the first movement, there’s a presentation of opening ideas, some development of them and a recapitulation of a kind; the second is a combination of slow movement and scherzo, and the finale comes across with some of the characteristics of a rondo and at one point quotes a rhythm from the opening movement – which is all really another way of saying that the writing is ingenious, subtle and many-faceted, and there are plenty of other examples of that in the piece.

Watkins said (in the pre-concert talk-in with Sir Mark and Radio 3 presenter Tom McKinney) that his music is about internal feelings and emotions – something that symphonies are often designed to do – but also to be a celebration of the Hallé and their virtuosity, so thoroughly living up to its branding. There are many precedents: Bartók’s and Lutosławski’s (the latter also in three movements with a double identity to the central one) among the most celebrated.

He also referenced Britten’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, and his opening movement begins with a focus on each of three sections of the orchestra – wind, strings and brass – each with its own theme-identity and accompanied by the rest as it makes its entrance. Alongside the virtuosity there’s a relaxed quality and lilting tunefulness, both apparent in the opening wind ensemble writing and in one way or another pervading the entire score. There’s a quieter, deeply felt and almost apprehensive sense in the strings’ first substantial time in the spotlight, and the brass contribution is rich and impactful … so the contrasts are not only of tone colour but also of feeling and emotional impact.

The central movement offers an evocative and simple melodic passage for strings and harp which we hear three times in all – the shimmering Hallé dolce sound from the strings, led by Roberto Ruisi, once again clearly present – with two scherzo-like passages interleaved. The first features limpid and delicate (albeit complex) sounds from the woodwind and celesta plus an intrusion by the brass; the second has the sound of brilliant trumpet tone (there are four of them in the otherwise fairly conventional symphony orchestra instrumentation) and a climax that was topped by powerful playing from Hallé principal Gareth Small. The movement ends very softly with the awestruck sound of the gong.

The last movement, Allegro vivace, again has the instruments at the top of the score leading off, this time in a several-times-returning dancing theme with a smattering of Scotch snaps, but there are also substantial pauses for introspection, and also a striking new sound created by harp and celesta in duet (with some added glockenspiel) against background wind lines. It all builds to an effective climax and, as with the ending of both Watkins’ two symphonies, doesn’t hang about once it’s got there.

“Probably my most exuberant and optimistic writing” said the composer of the work as a whole. He may have overlooked the extraordinary optimism of the Second Symphony’s conclusion, but that was of another time (written in mid-Covid) and this is still a very welcome breath of fresh air.

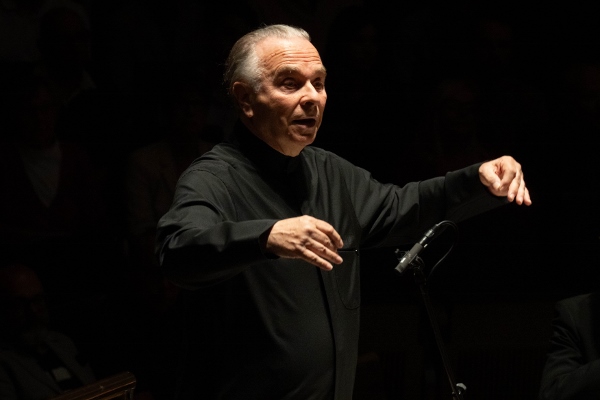

Fresh air may even have been its stimulus in some way, as Watkins knew his new work would be on the same bill as Richard Strauss’s Alpine Symphony. Sir Mark Elder (pictured), the Hallé’s conductor emeritus in his first return to the Bridgewater Hall bearing that honour, who was midwife to the Watkins world premiere with calm assurance and attentive care, was also in his element in this huge musical nature narrative. Strauss apparently said it would need 123 players, and though there may not have been quite that number on Saturday night there were certainly forces pretty close to it. It was Elder’s first time performing it with the orchestra he was in charge of for nearly 25 years, and he had his stamp on it as in the past, ensuring that a screen was visible with the descriptive titles Strauss gave to the episodes in the story, as he used to with other Strauss tone poems such as Don Quixote and Ein Heldenleben.

Sir Mark Elder (pictured), the Hallé’s conductor emeritus in his first return to the Bridgewater Hall bearing that honour, who was midwife to the Watkins world premiere with calm assurance and attentive care, was also in his element in this huge musical nature narrative. Strauss apparently said it would need 123 players, and though there may not have been quite that number on Saturday night there were certainly forces pretty close to it. It was Elder’s first time performing it with the orchestra he was in charge of for nearly 25 years, and he had his stamp on it as in the past, ensuring that a screen was visible with the descriptive titles Strauss gave to the episodes in the story, as he used to with other Strauss tone poems such as Don Quixote and Ein Heldenleben.

He enjoys the picture-painting in the piece: really a tone poem of a 12-hour-long ascent and descent in the mountains, rather than a conventional symphony. There’s a bleary-eyed early start in darkness, a sunrise, birdsong, a babbling brook and thunderous waterfall, cowbells clonking in the upper pastures, a glorious view from the top, mists arising, a surprise thunderstorm and final return to base as night resumes.

But there’s also a generous overlay of musical thoughtfulness, as the expedition becomes a source of philosophical rumination (along with that of the cows) to the climber, and a symbol of human striving, achievement, frustration and acceptance.

The opening was magical, string figurations played with precision and almost eery alongside the Wagnerian weight of the brass chorus – the Alpine quest was clearly to be daunting – but the off-stage enthusiasm of 12 horns in hunting mode brought relaxation and confidence, with warm, even lush-sounding string tone, and the wind, as in the Watkins, were in beautifully watery voice.

The account of the climbers taking the wrong path was scarily vivid – Gareth Small, refreshed no doubt by his own communing with nature at a Cheshire garden centre in the afternoon (we have spies everywhere) again on top form. And, after a quietly awe-struck moment as the view from the summit is first glimpsed (Stéphane Rancourt’s oboe eloquent here) the pride of conquest was expressed in a magnificent brass tutti and glowing strings.

The advent of the thunderstorm is the main event in the downward trek, the organ (Darius Battiwalla) effectively ominous and the timpani and bass drum entries dramatic. It’s a phenomenon you encounter in the Alps that a storm can be brewing in a neighbouring valley while you’re still in sunshine on your own pathway – Strauss knew that and caught the atmosphere of apprehension when you don’t know whether it’s coming your way or not.

Once down to valley level, albeit soaked to the skin, the wanderers’ experience of sunset and twilight (remember in mountains it takes a long time after the sun has hidden itself before the light finally dies) was depicted in glorious warmth, from principal horn Laurence Rogers, Gareth Small’s trumpet and the entire wind section. It was a beatific vision in music and the last pages had a quality of heartfelt thankfulness – positivity and optimism again to end the day.

- To be broadcast on Radio 3 on 5 June

- More classical reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

Willis-Sørensen, Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra, Wilson, Cadogan Hall review - romantic resilience

Passion, and polish, from Kyiv's musical warriors

Willis-Sørensen, Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra, Wilson, Cadogan Hall review - romantic resilience

Passion, and polish, from Kyiv's musical warriors

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

BBC Proms: Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - defiantly introverted Mahler 5 gives food for thought

Chief Conductor in Waiting has supple, nuanced chemistry with a great orchestra

BBC Proms: Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - defiantly introverted Mahler 5 gives food for thought

Chief Conductor in Waiting has supple, nuanced chemistry with a great orchestra

Dunedin Consort, Butt / D’Angelo, Muñoz, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tedious Handel, directionless song recital

Ho-hum 'comic' cantata, and a song recital needing more than a beautiful voice

Dunedin Consort, Butt / D’Angelo, Muñoz, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tedious Handel, directionless song recital

Ho-hum 'comic' cantata, and a song recital needing more than a beautiful voice

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

This year's big anniversary celebrated with a pair of boxes, plus clarinets, pianos and sacred music

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

This year's big anniversary celebrated with a pair of boxes, plus clarinets, pianos and sacred music

BBC Proms: Liu, Philharmonia, Rouvali review - fine-tuned Tchaikovsky epic

Sounds perfectly finessed in a colourful cornucopia

BBC Proms: Liu, Philharmonia, Rouvali review - fine-tuned Tchaikovsky epic

Sounds perfectly finessed in a colourful cornucopia

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Add comment