Classical CDs: Bells, whistles and bowing techniques | reviews, news & interviews

Classical CDs: Bells, whistles and bowing techniques

Classical CDs: Bells, whistles and bowing techniques

A great pianist's early recordings boxed up, plus classical string quartets, French piano trios and a big American symphony

Michel Béroff: Complete Erato Recordings (Erato)

Michel Béroff: Complete Erato Recordings (Erato)

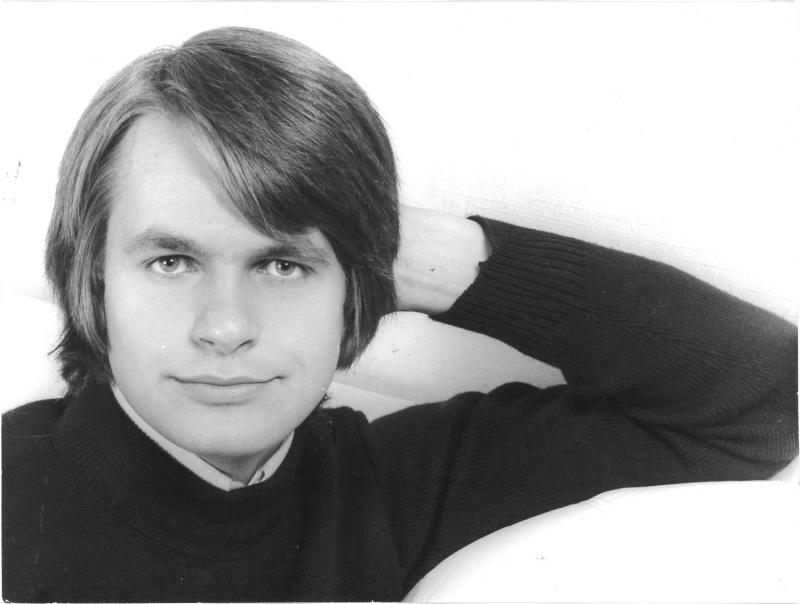

My associating French pianist Michel Béroff with ‘modern’ music says more about my age than it does about Béroff’s actual specialities. If you were looking for Messiaen in an early 1980s record library you’d probably find his EMI LPs of Turangalîla, the Quatour pour la fin du Temps and the Vingt Regards sur l'Enfant-Jésus on the shelves, the last named a work which Béroff played extracts from to its composer in 1961, at the age of 11. The mind boggles; as it does when you learn that the earliest recording in this 42-disc box is the Quatuor, a 1968 classic taped in Abbey Road when Béroff was just 18. The performance holds up well, Béroff unfazed by his three starry collaborators, fully comfortable with the work’s technical and emotional challenges. I’d not heard his recording of Messiaen’s youthful set of Préludes before, and it’s a find, the dry Salle Wagram acoustic making the colours even more vivid. Béroff teamed up with André Previn and the LSO for the solo piano role in the Turangalîla-Symphonie, a bold, exuberant reading in stunning analogue sound.

Other 20th century treats include a cycle of Prokofiev piano concertos made with Kurt Masur and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra in 1973, Béroff’s propulsive, witty playing heard against plenty of piquant orchestral detail. Recordings of Concertos 4 and 5 were thin on the ground then, and Béroff is a charismatic guide. The little Overture on Hebrew Themes is a charmer, and we get five of the piano sonatas, the two violin sonatas and the Visions Fugitives. Two discs contain a generous selection of Bartók miniatures, the Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm which close Mikrokosmos superbly done.

Other 20th century treats include a cycle of Prokofiev piano concertos made with Kurt Masur and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra in 1973, Béroff’s propulsive, witty playing heard against plenty of piquant orchestral detail. Recordings of Concertos 4 and 5 were thin on the ground then, and Béroff is a charismatic guide. The little Overture on Hebrew Themes is a charmer, and we get five of the piano sonatas, the two violin sonatas and the Visions Fugitives. Two discs contain a generous selection of Bartók miniatures, the Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm which close Mikrokosmos superbly done.

There’s a complete set of Stravinsky’s solo piano music including a thrilling account of the Three Movements from Petrushka and a disc made with Seiji Ozawa and the then-new Orchestre de Paris: Stravinsky’s Capriccio and Concerto for piano and wind instruments really should be heard more often, and there’s a cogent account of the thorny, late Movements for Piano and Orchestra. Six Debussy discs contain some superb things: the complete Preludes, Études and Images plus a collection of melodies with Barbara Hendricks. All great, though I’ve returned most often to a disc of Debussy’s music for piano duet and piano 4-hands, Béroff teamed with fellow EMI artist Jean-Philippe Collard. Debussy’s unfinished Symphony in B minor, a single movement for piano 4-hands, is intriguing but uncharacteristic.

There’s a complete set of Stravinsky’s solo piano music including a thrilling account of the Three Movements from Petrushka and a disc made with Seiji Ozawa and the then-new Orchestre de Paris: Stravinsky’s Capriccio and Concerto for piano and wind instruments really should be heard more often, and there’s a cogent account of the thorny, late Movements for Piano and Orchestra. Six Debussy discs contain some superb things: the complete Preludes, Études and Images plus a collection of melodies with Barbara Hendricks. All great, though I’ve returned most often to a disc of Debussy’s music for piano duet and piano 4-hands, Béroff teamed with fellow EMI artist Jean-Philippe Collard. Debussy’s unfinished Symphony in B minor, a single movement for piano 4-hands, is intriguing but uncharacteristic.

Collard became a regular collaborator, the pair’s discography including more French music by Milhaud, Saint-Saëns and Bizet, a dazzling version of Dukas’s L’Apprenti sorcier in the composer’s two-piano transcription a real stunner. Their Ravel compilation contains a delicious Ma mère l'Oye and unsettling, demonic La Valse. A set of Brahms Hungarian Dances in piano-duet form sparkles, as does an entertaining album containing both sets of Dvořák Slavonic Dances, as exciting and idiomatic as any orchestral versions I’ve heard.

Béroff’s excursions into ‘standard’ repertoire are impressive, a terrific disc of Liszt piano concertos the product of a second visit to Leipzig and Kurt Masur. Do sample Béroff’s version of Liszt’s Totentanz, featuring some magnificently unrefined lower brass, and his powerful, imaginative reading of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. There are three discs of solo Schumann, and two containing Bach concertos for two, three and four pianos, Collard again among the collaborators. A disc of previously unpublished material places Bach’s Overture in the French Style alongside a pair of late Beethoven sonatas, and there’s a fascinating collection of works for the left hand, the result of Béroff having developed focal dystonia in the mid-1980s. Happily he made a full recovery; the Dukas and Bizet disc mentioned above (taped in 1994) shows him on stunning form. This is a seriously desirable set, the performances ranging from very good to excellent, the remastered sound warm and clear. Stephan Schwartz-Peters’ booklet essay provides a decent overview of Béroff’s early career, the individual discs retaining EMI’s original sleeve art.

Béroff’s excursions into ‘standard’ repertoire are impressive, a terrific disc of Liszt piano concertos the product of a second visit to Leipzig and Kurt Masur. Do sample Béroff’s version of Liszt’s Totentanz, featuring some magnificently unrefined lower brass, and his powerful, imaginative reading of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. There are three discs of solo Schumann, and two containing Bach concertos for two, three and four pianos, Collard again among the collaborators. A disc of previously unpublished material places Bach’s Overture in the French Style alongside a pair of late Beethoven sonatas, and there’s a fascinating collection of works for the left hand, the result of Béroff having developed focal dystonia in the mid-1980s. Happily he made a full recovery; the Dukas and Bizet disc mentioned above (taped in 1994) shows him on stunning form. This is a seriously desirable set, the performances ranging from very good to excellent, the remastered sound warm and clear. Stephan Schwartz-Peters’ booklet essay provides a decent overview of Béroff’s early career, the individual discs retaining EMI’s original sleeve art.

Bliss: The Composer Conducts Arthur Bliss (cond), John Ogdon (piano), BBCSO et al (SOMM)

Bliss: The Composer Conducts Arthur Bliss (cond), John Ogdon (piano), BBCSO et al (SOMM)

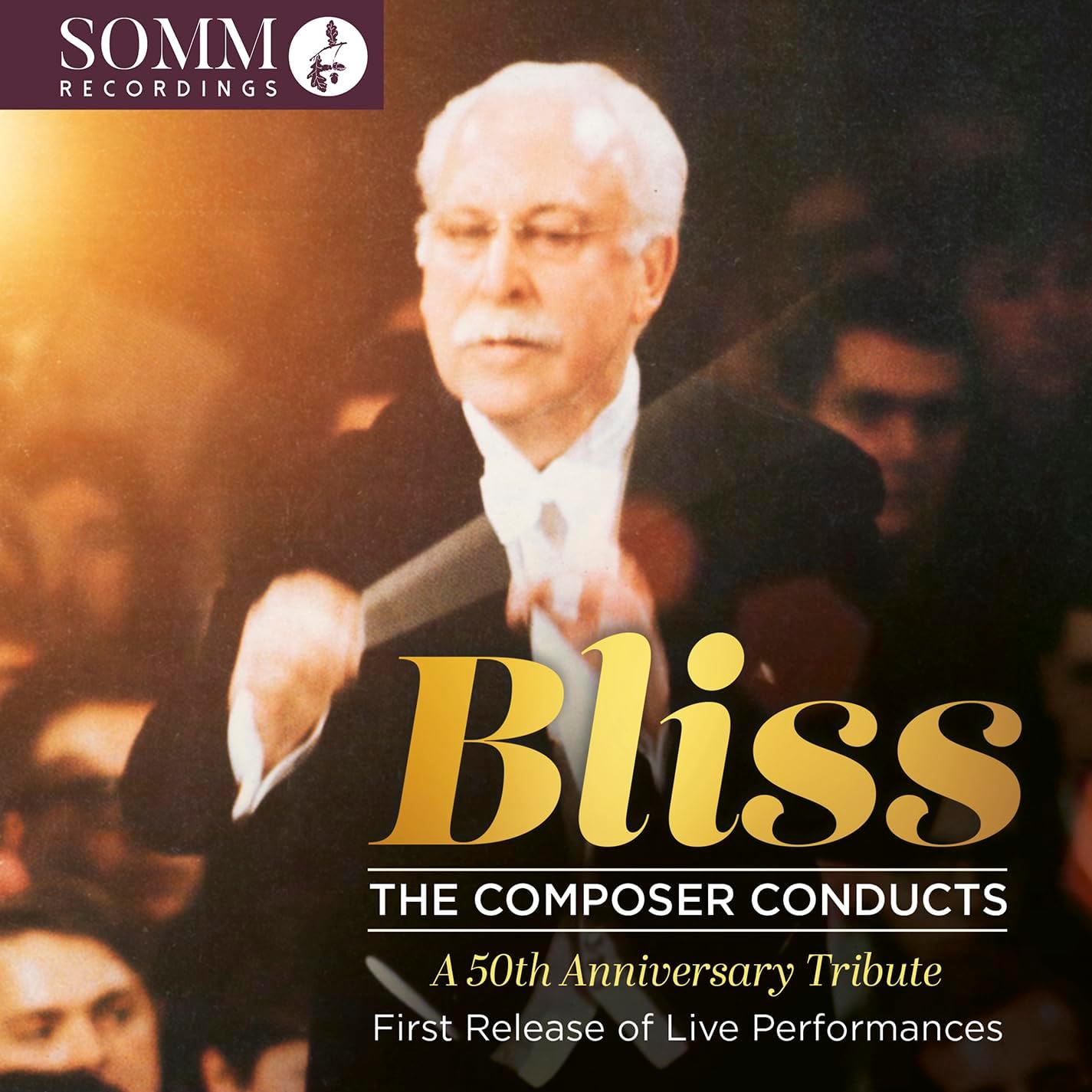

This year is the 50th anniversary of the death of Sir Arthur Bliss, but there hasn’t been too much activity of note to mark the occasion. The RPO and Peter Donohoe played his Piano Concerto in London and there are a couple of things in the Proms, but for the main part Bliss remains in the shadows, despite the fact that his best music is of enduring merit. Although Bliss often took up the baton for his own music, there were relatively few commercial recordings of him as a conductor. This new double album from SOMM releases for the first time archive recordings made at live concerts in the 1960s, brilliantly remastered by Lani Spahr. It is a must-have for the library of any Bliss fan, and throws a fascinating light on some important pieces.

A Colour Symphony was commissioned by Edward Elgar for the Three Choirs Festival in 1920, when Bliss was still in his 20s, and is one of his finest pieces, despite its shambolic premiere that brought the composer to despair. The present recording comes from a Proms performance in 1961 to mark Bliss’s 70th birthday. It is clear that the music still invigorates him and the London Symphony Orchestra, who give an energetic performance. The sound – so important in a “colour symphony” – is not bad, making allowances for the venue and live performance. It doesn’t have the gleam and polish of later studio versions (my favourite is Vernon Handley with the Ulster Orchestra) but holds up better than Bliss’s own studio version with the LSO from 1955.

The Piano Concerto was premiered in the US in 1939 and the present recording, with soloist John Ogdon, is from the Proms celebration of Bliss’s 75th birthday in 1966. Hearing it live recently, it felt a bit stodgy and lacking in big moments, but the electricity of Ogdon’s performance brings it to life and makes light of the extreme difficulties of the piano part. The opening is spectacular and the playing characteristically mercurial, from the fireworks of the first movement to the inwardness of the second.

Morning Heroes is the most interesting piece here. Bliss and his brother both served in WWI and Kennard was killed. In 1930 he wrote a large-scale piece for orchestra, chorus and orator, on the subject of Hector and Andromache but really about Bliss and his brother. The present recording is its only performance at the Proms, from 1968, garlanded with Donald Douglas’s stirring, declamatory narration – which is not without subtlety and shading – and very different from Samuel West’s understated, intimate reading on the 2015 Chandos recording. But I like the heroism, it seems to work with this properly heartfelt, anguished piece. I loved it, as I did with the Concerto for Two Pianos, in its version for the three hands of Cyril Smith and Phyllis Sellick, taped at a 1969 Prom. It has a light-hearted tone in common with the Malcolm Arnold concerto for the same combination which was premiered in the same concert and which I probably prefer. But the Bliss is good to hear, conducted by the composer, with the brass and timpani coming through well in this excellent remaster. Bernard Hughes

Haydn: String Quartets, Op. 33, ‘Russian’: Nos 4–6 Chiaroscuro Quartet (BIS)

Haydn: String Quartets, Op. 33, ‘Russian’: Nos 4–6 Chiaroscuro Quartet (BIS)

When things are meant to happen, they can happen fast, even in the world of string quartets. “Dear all,” said a Facebook post in French in late June 2024. “It is with great emotion that we announce the end of the Confluence Quartet.” Within days of that, it became public that the Confluences’ first violin, Montpellier-raised, Menuhin School-trained Charlotte Saluste-Bridoux, would be joining the Chiaroscuro Quartet, founded in 2005, as its new second violin. Saluste-Bridoux, a YCAT and Concert Guild International prizewinner, and a Masters student of Ibragimova at RCM until 2022, who has described herself as being "a lot like a violin – quite small, portable, and loud!", replaced Pablo Hernán Benedí who had been with the quartet since 2010. A month after the news, this new Haydn recording was made, with the new line-up, at the Menuhin School in Surrey.

The Chiaroscuros have been cultivating a particular sound for nearly two decades. As a text accompanying one of their early releases states, the quartet “uses gut strings and historically accurate bows and bowing techniques, producing a sound with sharp, dramatic attacks and little vibrato.” It is a world away from the world of definitive beauty which quartets would sit down to create so painstakingly in the latter half of the twentieth century (the three members of the Chiaroscuros who can stand up, actually do, and they did so for this recording).

This is bold and characterful playing, but perhaps what it has above all is a feeling of being free, fresh and experimental...and I am wondering if that isn’t enhanced by the brand-new arrival of a sparky, younger player at the heart of the group. The musicianship level and reactiveness and quality of ensemble are astonishing, but it is applied to make in-the-moment freshness. Listen to the wonderful tempo flexibility in the opening section of the final Allegretto movement of the G Major quartet (nicknamed ‘Gli Scherzi’ or “How Do You Do?” and the best-known of the three here) with its variations on a siciliano. The Chiaroscuros certainly bring out what Richard Wigmore in the detailed sleeve note calls the “graceful fluidity of texture” but there is a lot more besides. I loved the freedom and the time they give to first the viola and then the cello to get their finger-busting in the last variation done, so that all four can pounce gleefully and forcefully together onto the final ‘Presto’ section.

For astonishing sounds to make the listener’s jaw drop, try the kittenish, pleading melody of the central section ‘Scherzo. Allegretto’ second movement of the B Flat Quartet No.4. Or for an object lesson in the value of dozens of little silences in a melodic line, the ensuing ‘Largo’ movement is just mesmerising. One critic noted that the Chiaroscuros’ first volume of Haydn Op. 33, recorded with the old line-up and released in 2023, was ‘an extraordinarily accurate reading that goes straight to the heart of the works.’ This second volume, I would argue, doesn’t have that aesthetic at all. It is raw, brash, light-footed...and wonderful. Sebastian Scotney

Wynton Marsalis: Blues Symphony Detroit Symphony/Jader Bignamini (Pentatone)

Wynton Marsalis: Blues Symphony Detroit Symphony/Jader Bignamini (Pentatone)

It’s sobering to realise how long Wynton Marsalis has been on the scene; I can remember the stir caused by his debut CBS LP featuring trumpet concertos by Haydn and Hummel. That disc, released in 1984 still sounds superb, Marsalis’s subsequent career taking in composition, jazz and education work. The Blues Symphony received its first performance in 2015, and this is already its second recording. Getting orchestras to let their hair down can be a tricky business. The likes of Bernstein and Previn managed it in the past. Andrew Litton and John Wilson have the gift, and on the basis of this recording, Italian conductor Jader Bignamini has it too. Plus, there’s something fitting about a work so steeped in decades of American popular music being performed by an ensemble based in a city so pivotal to the genre’s development, Bignamini’s Detroit Symphony letting rip in all the right places.

This is a big, seven-movement work, opening with an evocation of revolutionary-era military bands and finishing up in the 21st century. Possibly too big – each separate movement is appealing. “Born in Hope” starts with piccolos impersonating fifes over a 12-bar blues chord sequence, growing into a punchy march which becomes as oppressive as it’s exciting. “Reconstruction Rag” features pastiche 19th century popular music, the scoring suggesting both Ives and Mahler. Most affecting is the central “Southwestern Shakedown”, some deliciously cool brass writing the prelude to a “Saturday night straight-up dance shuffle” dressed in Gershwin-esque colours. Bignamini’s players are terrific here, even if the melody never reaches Gershwinian heights. “Big City Breaks” could be an offcut from West Side Story, the syncopated rhythms full of punch, the assorted whistles, bells and siren effects effective. “Danzon y Mambo, Choro y Samba” is fun if over-extended, the symphony ending with a frenetic “Dialogue in Democracy” and a punchy, dissonant close. Is it a symphony, or a sequence of linked tone poems? More the latter, I think; I found myself returning frequently to savour individual movements after listening to this hour-long work in one sitting. It’s good to see the players listed in the booklet: the six percussionists deserving a shout out. And, how good it is to welcome a huge orchestral work that’s so affirmative in tone, Marsalis writing in the booklet that “when you dance and find a common community through groove, better times will be found.” Let’s hope he's right.

Mozart: Piano Sonatas Angela Hewitt (Hyperion)

Mozart: Piano Sonatas Angela Hewitt (Hyperion)

Angela Hewitt’s 50th album for Hyperion completes her survey of the Mozart piano sonatas, here covering the last sonatas plus the extraordinary C minor Fantasia K475, the Variations on “Ah, vous dirai-je maman” and, if that wasn’t enough, four sundry movements without a proper home, but that deserve to be heard.

The Fantasia is one of the most extraordinary exercises in deferred gratification, running for 13 minutes with essentially no cadences that establish that we are actually in C minor until the very end. It is constantly on the move harmonically, and Hewitt captures the restlessness, while still maintaining her customary cool. I wasn’t sure about following it with the C minor sonata K457 – the sonatas are presented in sequential order, but didn’t have to be – as I would have welcomed a bit of light and shade at that point in the disc. This came instead with the crystalline textural simplicity of K533, in F major, which Hewitt allows to meander along its way without the grandeur – or mock-grandeur – of the C minor sonata.

The famous sonata in C originally published as “sonata facile”, is often played by young pianists, but is by no means as technically easy as the soubriquet suggests. The simplicity comes in the breezily innocent musical material, which Hewitt freely embellishes in a way I’m sure Mozart would have approved of. The second movement is taken at a no-nonsense speed while the finale is taken at a sensible allegretto rather than a gallop.

Of the miscellaneous pieces, the brief Gigue K574 is the standout – Bachian in its contrapuntal athleticism, but with a sparkle that is pure Mozart. The Variations on “Ah, vous dirai-je maman” take the tune known in English as “Twinkle, twinkle, little star” and are a virtuoso compositional feat, moving from the most banal opening to concerto-like runs – and then, in variation 11, to a heart-rending aria. Hewitt’s version is probably my favourite of all I’ve heard – and there are some pretty nasty ones around: avoid, in particular, Lang Lang’s abomination. She is nimble and witty, characterising each variation clearly but never strives for effect, and adding runs and decorations that are in the spirit of the birth of this piece as a competitive improvisation.

The last two sonatas, in B flat and D respectively, date from 1789. The former has a gorgeous slow movement, which even though marked “adagio” is taken without any self-indulgence, and is all the more moving for that. The D major sonata K576 has none of the introspection of Beethoven’s last sonatas, but is as bright and cheerful as Mozart can be in its straightforwardly-textured outer movements. There is, though, introspection aplenty in the Adagio K540 and Rondo K511 that finish this lovely cycle: the Rondo dates from the time of the death of Mozart’s father, and is freighted with emotion that Hewitt recognises but doesn’t milk. This album, as with the other two, is highly enjoyable and recommended. Bernard Hughes

Weir/Beach: Choral Music Yale Schola Cantorum/David Hill (Hyperion)

Weir/Beach: Choral Music Yale Schola Cantorum/David Hill (Hyperion)

Judith Weir’s In the Land of Uz, premiered by the BBC Singers at the 2017 Proms, looks back nearly 30 years to her 1988 masterpiece, Missa del Cid, most notably in the use of a narrator. This gives the recounting of the Book of Job a gravity, but also a dramatic distancing. In this first recording, by the Yale Schola Cantorum under David Hill, who conducted the premiere, the narrator is Tommy Watson, who maybe gets involved in the action a bit too much: I might have preferred a more remote tone to point up the real musical drama, heard in Steven Soph’s touching tenor solo.

Weir’s setting of In the Land of Uz has a lot of variety, both in its use of solo voices emerging from the choral texture, but also the instrumental accompaniment of five solo instruments and organ (violist Gretchen Frazer is outstanding). It is perhaps a bit too diffuse – the jazzy third movement feels a bit out of place – and the strongest bits are definitely the choral sections, which wrestle with Job’s central dilemma: if God is all-good and all-powerful, why do evil and suffering exist? There are no firm answers, either theologically or musically, but the concluding movement, in which (spoiler alert) it all turns out ok for Job, the choral meditation, with dreamy viola obbligato, is Judith Weir at her best, and the Yale Schola Cantorum in fine voice.

I am less familiar with the work of Amy Beach, whose Canticle of the Sun is the companion piece for the Weir. Beach takes the words of St Francis of Assisi (translated by Matthew Arnold) to give thanks for the natural glories of creation, using choir, soloists and orchestra in a more orthodox manner than does Weir. Beach designed it to appeal to – and be performable by – amateur groups, and the piece succeeded in finding a place in the American choral repertoire in the mid-20th century. The choir and orchestra revel in the broadly Wagnerian writing, and the soloists all have their moments: soprano Juliet Ariadne Papadopoulos really takes wing in the second movement, and Peter Schertz is movingly plaintive in the sixth. The choir get their teeth into some meaty passages and it all sounds a lot of fun to sing, a distinctive American accent detectable in the music as well as in the performance. As with the Weir, which it sits alongside fascinatingly, the final movement is where it all comes together, dissolving from a big choral climax into the humblest of thanksgivings. Bernard Hughes

La Mer: French Works for Piano Trio – music by Saint-Saëns, Mel Bonis and Debussy/Beamish Neave Trio (Chandos)

La Mer: French Works for Piano Trio – music by Saint-Saëns, Mel Bonis and Debussy/Beamish Neave Trio (Chandos)

Nearly 30 years separate Saint-Saëns’ two piano trios. No. 1, written in 1864, is an expansive, sunny work. Its 1892 successor is darker and more ambitious, a large scale, five-movement piece which Saint-Saëns took much care over before allowing Durand to publish the first edition. A huge opening movement has a real symphonic sweep, its swinging 12/8 opening theme a distant cousin to the “Allegro moderato” of Saint-Saëns’ Symphony No. 3. It’s followed by a delicious “Allegretto” in 5/8 and 5/4, the lopsided metre brilliantly sustained, and a compact slow movement. An extended finale looks as if it’s about to wrap things up in a hard-earned E major before Saint-Saëns throws in a frenzied minor key coda. It’s a masterpiece, beautifully played here by the Boston-based Neave Trio. They follow it with a real rarity, Soir-Matin by Mel Bonis, a prolific fin-de-siecle composer whose 1905 Piano Quartet prompted Saint-Saëns to remark: "I never imagined a woman could write such music!" Soir-Matin, composed in 1907, is a beguiling two-part work that I’ve had on repeat for weeks. Listen to the final seconds of “Matin”, the music seemingly drifting out of sight – it’s exquisite stuff.

Sally Beamish’s ingenious recasting of Debussy’s La Mer as a piano trio closes this anthology. I’m a sucker for a good transcription, and this one ticks all the right boxes. It’s impossible to un-hear Debussy’s original if you know it well, but Beamish’s arrangement does sound like a genuine piano trio, the thematic material properly shared between the three protagonists. The soft opening is magical, pianist Eri Nakamura’s pedal notes just audible enough under violinist Anna Williams’s solo, and listen out for the blaze of sunlight which concludes the movement. “Jeux de vagues” glitters and shimmers, and the third movement’s final minutes are exciting and uplifting. I’d love to hear this live. An enticing anthology, superbly played and warmly recorded.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Kolesnikov, Tsoy / Liu, NCPA Orchestra, Chung, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - transfigured playing and heavenly desire

Three star pianists work wonders, and an orchestra dazzles, at least on the surface

Kolesnikov, Tsoy / Liu, NCPA Orchestra, Chung, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - transfigured playing and heavenly desire

Three star pianists work wonders, and an orchestra dazzles, at least on the surface

BBC Proms: Láng, Cser, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer review - idiomatic inflections

Bartók’s heart of darkness follows Beethoven’s dancing light

BBC Proms: Láng, Cser, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer review - idiomatic inflections

Bartók’s heart of darkness follows Beethoven’s dancing light

Weilerstein, NYO2, Payare / Dueñas, Malofeev, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - youthful energy and emotional intensity

Big-boned Prokofiev and Shostakovich, cacophonous López, plus intense violin/piano duo

Weilerstein, NYO2, Payare / Dueñas, Malofeev, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - youthful energy and emotional intensity

Big-boned Prokofiev and Shostakovich, cacophonous López, plus intense violin/piano duo

theartsdesk at the Three Choirs Festival - Passion in the Cathedral

Cantatas new and old, slate quarries to Calvary

theartsdesk at the Three Choirs Festival - Passion in the Cathedral

Cantatas new and old, slate quarries to Calvary

BBC Proms: Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, Kaljuste review - Arvo Pärt 90th birthday tribute

Stillness and contemplation characterise this well sung late-nighter

BBC Proms: Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, Kaljuste review - Arvo Pärt 90th birthday tribute

Stillness and contemplation characterise this well sung late-nighter

BBC Proms: Kholodenko, BBCNOW, Otaka review - exhilarating Lutosławski, underwhelming Rachmaninov

Polish composers to the fore in veteran conductor’s farewell

BBC Proms: Kholodenko, BBCNOW, Otaka review - exhilarating Lutosławski, underwhelming Rachmaninov

Polish composers to the fore in veteran conductor’s farewell

theartsdesk at the Pärnu Music Festival 2025 - Arvo Pärt at 90 flanked by lightness and warmth

Paavo Järvi’s Estonian Festival Orchestra still casts its familiar spell

theartsdesk at the Pärnu Music Festival 2025 - Arvo Pärt at 90 flanked by lightness and warmth

Paavo Järvi’s Estonian Festival Orchestra still casts its familiar spell

BBC Proms: Batsashvili, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Ryan Wigglesworth review - grief and glory

Subdued Mozart yields to blazing Bruckner

BBC Proms: Batsashvili, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Ryan Wigglesworth review - grief and glory

Subdued Mozart yields to blazing Bruckner

Add comment