Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress | reviews, news & interviews

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

This year's big anniversary celebrated with a pair of boxes, plus clarinets, pianos and sacred music

Shostakovich: Symphonies; Concertos; Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District Yuja Wang (piano), Baiba Skride (violin), Yo-Yo Ma (cello), Boston Symphony Orchestra/Andris Nelsons (DG)

Shostakovich: Symphonies; Concertos; Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District Yuja Wang (piano), Baiba Skride (violin), Yo-Yo Ma (cello), Boston Symphony Orchestra/Andris Nelsons (DG)

Shostakovich: The Symphonies Gürzenich-Orchester Köln/Dmitrij Kitajenko (Capriccio)

Here are two big Shostakovich boxes, released to mark the 50th anniversary of the composer’s death. Dmitri Kitajenko’s symphony cycle, a mixture of studio and live performances, was recorded between 2002 and 2004. Originally boxed up as a set of SACDs. Capriccio’s budget priced reissue gives us just the stereo mix, the engineering consistently impressive across three different venues. Andris Nelsons’ live performances were taped between 2015 and 2024, his set including the six concertos and the opera Lady Macbeth. Both boxes contain great things but serve as a reminder that it’s rare for one conductor to get everything right.

Nelsons recorded the middle-period symphonies first, his readings of nos. 4 to 11 spectacularly well-played and brilliantly engineered. It’s good to hear an orchestra as plush as the Boston Symphony letting rip, the scarier outbursts in Symphonies 7 and 8 really hitting home. The string playing in No. 5’s great “Largo” is exquisite, and No. 6’s long, enigmatic opening movement is brilliantly sustained, followed by pin-sharp performances of the two scherzos. I really enjoyed Nelsons’ 9th too, the third movement’s blend of exhilaration and panic perfectly judged, the bassoon soliloquy before the finale providing a welcome moment of gravitas. Symphony No. 10 is as good as any recent performance I’ve heard, the closing minutes exultant. It won’t supplant Karel Ancerl’s sizzling 1955 DG recording in my affections, Ancerl one of the few conductors who actually observes the moderato tempo marking in the first movement. Nelsons takes nearly 26 minutes, Ancerl barely 20.

The other symphonies aren’t as distinctive, though No. 14 has decent solo singing from soprano Kristine Opolais and bass Alexander Tsymbalyuk, and the final pages of No. 15 are affecting. Nelsons includes some orchestral extras, the suites from incidental music which Shostakovich composed for stage productions of Hamlet and King Lear brilliantly characterised. What else? I enjoyed Yuja Wang’s percussive, full-blooded accounts of the two piano concertos, and Baiba Skride is especially good in the neglected Violin Concerto No. 2. Yo-Yo Ma’s new version of the Cello Concerto No. 1 isn’t as exciting as his early 1980s Sony recording, he and Nelsons better in the haunting, introspective sequel. Nelsons’ live Lady Macbeth fills three discs instead of the usual two and can’t match the Rostropovich studio recording in terms of intensity, despite Opolais’s performance in the lead role.. No libretto is provided, though you’ll find one online easily enough.

Kitajenko is less flamboyant but interpretatively more consistent. Compare his Symphony No. 1 with Nelsons’, Kitajenko’s swifter tempi suiting the work so much better. Shostakovich’s epic 4th Symphony is excellent, Cologne’s Gürzenich-Orchester playing out of their collective skins, and No. 5 is sober but powerful, the first movement’s quiet coda really unsettling. The zippier moments in Nos. 6 and 9 showcase some virtuosic solo wind playing, and the brass in No. 7 have weight. This 8th is very broad, its first movement lasting almost 30 minutes, but Kitajenko prevents the piece from sprawling. Listen to the tam-tam at the start of the great “Largo”, and at how tenderly the Cologne players negotiate the shift to C major at the movement’s end, as if they’re cautiously emerging from a dungeon into hazy light.

Kitajenko is less flamboyant but interpretatively more consistent. Compare his Symphony No. 1 with Nelsons’, Kitajenko’s swifter tempi suiting the work so much better. Shostakovich’s epic 4th Symphony is excellent, Cologne’s Gürzenich-Orchester playing out of their collective skins, and No. 5 is sober but powerful, the first movement’s quiet coda really unsettling. The zippier moments in Nos. 6 and 9 showcase some virtuosic solo wind playing, and the brass in No. 7 have weight. This 8th is very broad, its first movement lasting almost 30 minutes, but Kitajenko prevents the piece from sprawling. Listen to the tam-tam at the start of the great “Largo”, and at how tenderly the Cologne players negotiate the shift to C major at the movement’s end, as if they’re cautiously emerging from a dungeon into hazy light.

Alas, Symphony No. 10’s “Moderato” is too much slow for my liking and Kitajenko’s steady tempo in the finale’s faster section prevents the music from ever catching fire. No. 11 is superb, though, and I’ll admit to having enjoyed this No. 12. Having the Prague Philharmonic Chorus really helps Symphonies 2, 3 and 13, bass Arutjun Kotchinian imposing in “Babi Yar”, and joined by soprano Marina Shaguch in No.14. 15 is impressive, with some sonorous brass providing the last movement’s Wagner quote and a perfectly judged coda. Documentation is good, the original releases’ sleeve essays handily squeezed into a single thick booklet. Both box sets represent really good value. Nelsons’ package contains enticing extras but Kitajenko is a more reliable guide to the symphonies. Next up is Gianandrea Noseda’s LSO Live Shostakovich cycle, due for release in a few months’ time.

Ben Folds Live with the National Symphony Orchestra Ben Folds, National Symphony Orchestra/Steven Reineke (John F Kennedy Center)

Ben Folds Live with the National Symphony Orchestra Ben Folds, National Symphony Orchestra/Steven Reineke (John F Kennedy Center)

This album only really sneaks into the Classical column, as an orchestral take on the songs of Ben Folds, a singer-songwriter who has been entertaining me for thirty years since he first emerged, like Billy Joel’s punkish kid brother in the 90s. His career has had great range, including, alongside ‘straight’ pop albums, films scores, a piano concerto – and, just this week, songs for the new Peanuts musical. For eight years he served as Artistic Adviser to the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington DC, resigning in February on the same day Donald Trump personally took over management of the Kennedy Center. This release is his final collaboration with the orchestra, captured in live performance in October 2024.

Given that Folds’ songs are mainly piano-led – he is a quite extraordinary pianist – it is perhaps surprising how well so many of the songs translate to orchestra. Folds sings, and plays the piano on some tracks, but it is the orchestra that is the focus. The songs largely come from later in his career, including a couple that were orchestral in their original guises. The best of this collection come from his most recent full album, 2023’s What Matters Most, including the opener, “But Wait, There’s More”, which is brilliantly scored, as if the original is just a sketch for this expansion. It’s a shame that the CD doesn’t give any orchestrator credits at all. A bit of online burrowing identifies the album’s orchestrators as Jherek Bischoff, Alex Turley, Eric Allen, and Rob Moose, and they deserve to be more front and centre. Heartbreakingly beautiful – and heartbreakingly sad – is “Kristine From the 7th Grade”, which examines the phenomenon of lockdown radicalisation through an exquisite waltz. It makes me cry.

The riotous “Effington” is one of Folds’ most infectious creations, here with a motoric rhythm propelled by snare drum, and it works well with a choir and audience participation. Likewise “You Don’t Know Me”, where Folds is joined (as on the album version) by Regina Spektor, as a song about a dysfunctional relationship becomes a feelgood singalong with marching strings and a tinkly celesta interlude.

There is introspection on “Still Fighting It”, with gorgeous horn and trumpet spots, and “Landed”, where Folds’ singing is as good as ever, and the orchestra is given full rein, conductor Steven Reineke allowing just the right about of sentimentality. If you don’t know Ben Folds this album is a good place to start – although I might also recommend the recent What Matters Most, or for something older, Songs for Silverman – and it is testament to the varied work of the National Symphony Orchestra in uncertain times for them. Bernard Hughes

Wonderings and Other Revelations – chamber works and songs by Edith Hemenway, Thomas Oboe Lee et al Nancy Braithwaite (clarinet), Claron McFadden (soprano), Vaughan Schlepp (piano) (Etcetera)

Wonderings and Other Revelations – chamber works and songs by Edith Hemenway, Thomas Oboe Lee et al Nancy Braithwaite (clarinet), Claron McFadden (soprano), Vaughan Schlepp (piano) (Etcetera)

Wonderings and Other Revelations is the apt title for clarinettist Nancy Braithwaite’s second album for the Dutch/Belgian label Etcetera. Whereas the first (To Paradise for Onions, 2019), was an overdue exploration of the work of the then 92-year-old American composer Edith Hemenway, this new release casts the net wider and represents a broader picture, including several works which Braithwaite herself – also the producer of the album – has either commissioned or inspired.

Edith Hemenway, an American composer in the lineage of Stephen Foster and Aaron Copland, died in 2023, and the works presented here are an eloquent memorial to her. Hemenway’s long and influential friendship with Braithwaite began when the clarinettist, still in her early twenties, was principal player in the Savannah (Georgia) Symphony Orchestra. The title track “Wonderings” is a lyrical cello piece of just under five minutes, and one of the highlights of the album is some very appealing songs by Hemenway to texts by Maya Angelou, Emily Dickinson and others, the vocal part ideally suited to the bright and agile soprano voice of the excellent Claron McFadden.

Composer Thomas Oboe Lee, another long-term friend of Braithwaite, has one of those life stories you really couldn’t or wouldn’t make up. Born in Beijing in 1945, he spent his teens and early twenties in Sao Paulo where his jazz flute skills allowed him to ride the bossa nova wave alongside luminaries such as Chico Buarque. Then followed a move to Boston, to composing and teaching composition – the touching story of his first collaboration with Braithwaite is well told. In the time since he settled there, he has been a multiple Guggenheim and NEA awardee. The work here, Yo Picasso, is a fascinatingly varied quartet for clarinet, viola, cello and piano in five fleeting movements drawing inspiration from periods in the painter’s creative life.

From the other pieces on the album, the listener starts to put together a portrait of the clarinettist, and the album booklet eloquently tells the stories of how her own life and musical career have intersected with those of the composers whose works are included. Braithwaite moved from her native Illinois to Holland in the early 1980’s, and the centrepiece is a virtuoso solo Sonata from 1985 by the ‘conductor, pianist, organist, composer and church musician’ who was to become her husband, Oane Wierdsma (1954-2008). In Braithwaite’s focused and assertive tone I think I can hear an echo of her one-time teacher, the eminent Larry Combs whose three decades as principal clarinet of the Chicago Symphony are the stuff of legend, although Braithwaite has taken the use of fast vibrato rather further than Combs did – it does take a bit of getting used to. She also studied with Walter Boeykens, and was herself a teacher for 33 years at Codarts in Rotterdam. She plays on, and also endorses, that rarity of an instrument, the Uebel Superior, a Boehm system instrument made in Germany. The recording is superb – venues include a favourite of Dutch musicians, the Westvest kerk in Schiedam – and the booklet, with all the song texts and much else included, has been carefully, thoughtfully, lovingly assembled. Sebastian Scotney

Chromatic Renaissance EXAUDI Vocal Ensemble/James Weeks (Winter & Winter)

Chromatic Renaissance EXAUDI Vocal Ensemble/James Weeks (Winter & Winter)

I only recently reviewed EXAUDI, an album of contemporary music utterly different from this, and this speaks to the twin comfort zones of the group, in the very new and very old. They give new music a sense of substance and permanence, while making the old sound novel, and never more so than in this album exploring music of the “chromatic Renaissance” of the mid-1500s: composers pushing the boundaries of what was possible within the pre-tonal harmonic system of the time. It is a heady and even disorientating listen, a bit like walking on a swaying ship’s deck: on the one hand the chords are familiar types, but they follow each other in such unlikely progressions that it can be dizzying.

The first track is one of the most extreme: Orlando di Lasso’s Timor et tremor. Within seconds we are whisked into a world or swirling harmonic uncertainty. Here it is at the service of a text expressing “psychic distress” although also widely used to represent eroticism, as in the languorous Anna mihi dilecta. There are also pieces by Cipriano de Rore, Luca Marenzio and Luzzascho Luzzaschi – of which Cipriano’s bleakly beautiful O Sonno is perhaps the pick.

But the really extraordinary stuff comes in the work of two less well-known composers, Vincente Lusitano (now considered to be the earliest published Afro-descendant composer) and Nicola Vicentino, who had a famous public debate over the issue of harmonic experimentation. Although Lusitano took the traditionalist side, he also created perhaps the strangest and most avant-garde pieces on this disc, Heu me, Domine, which is made up of creeping vocal lines going up and up the chromatic scale, a degree of total chromaticism not seen again for another three-and-a-half centuries. The debating voice of adventure, Vicentino, is represented only by the fragments of his work that survive in a treatise he wrote to argue his point. His big idea was to create a microtonal scale of 31 degrees, and the resulting music – sung with pinpoint precision by EXAUDI – is haunting, utterly peculiar and frighteningly modern.

An EXAUDI album is always a must-listen, put together with impeccable scholarship and musical sensitivity, with beautiful presentation by Winter & Winter. And the singing is intoxicating – although listening to the whole thing straight through might leave you feeling dangerously squiffy. Bernard Hughes

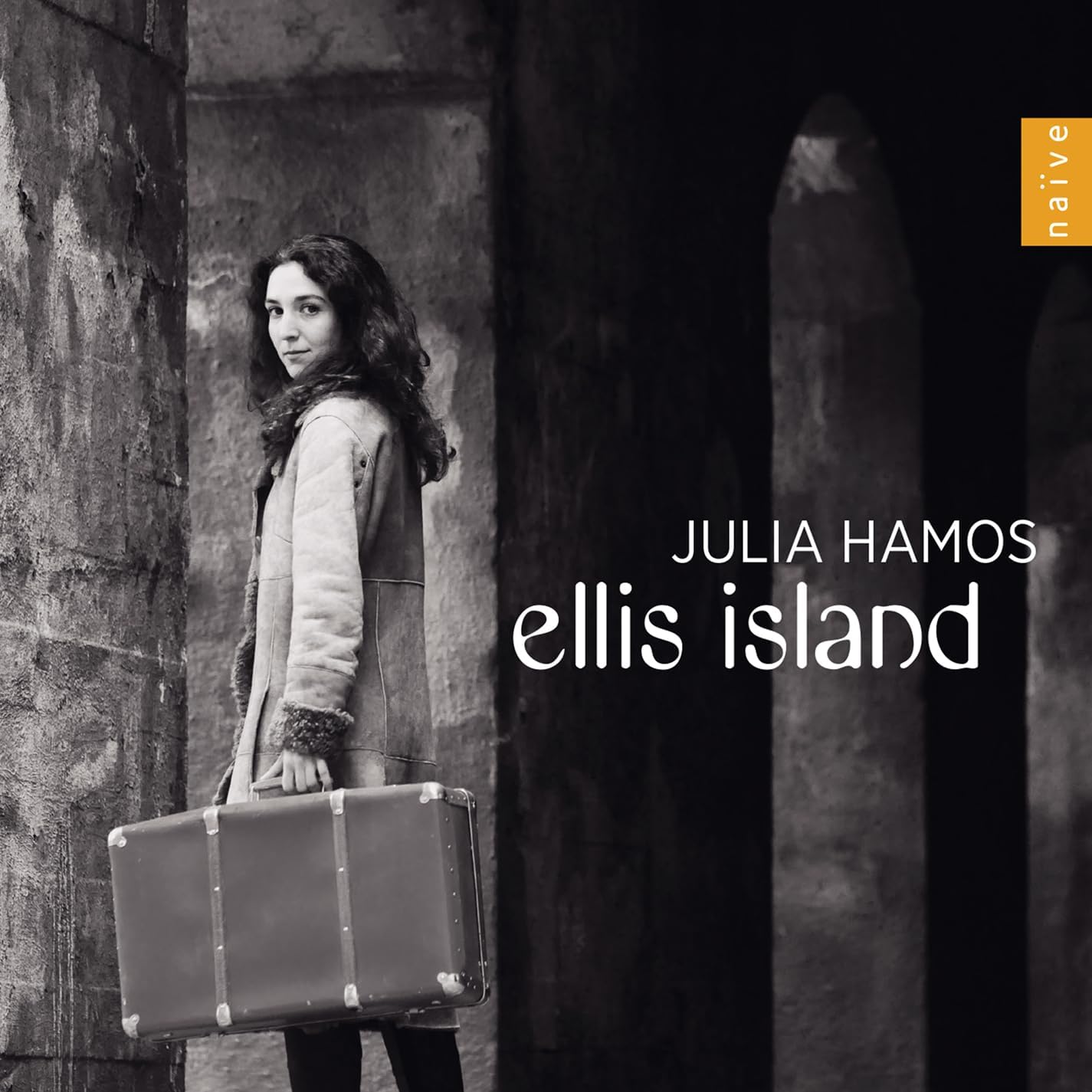

Ellis Island – music by Bartók, Kurtág, Ligeti, Mingus, Monk and Schubert Julia Hamos (piano) (Naïve)

Ellis Island – music by Bartók, Kurtág, Ligeti, Mingus, Monk and Schubert Julia Hamos (piano) (Naïve)

I’m a sucker for a well-planned recital disc and Julia Hamos’s anthology ticks all the right boxes. New York’s Ellis Island was where millions of US immigrants were processed between 1892 and 1954, and is an apt title for an album celebrating the pianist’s Hungarian and American heritage. Hamos opens with one of György Kurtág’s playful Játékok (Games), the rising and falling swoops suggesting an excited child running their fingers up and down the keyboard. The vertiginous final descent caught me unawares. Hamos adds Kurtág’s early 8 Klavierstücke, fiendish but dazzling miniatures, most lasting less than a minute. She finds rapt mystery in the quieter moments (sample the tiny “Calmo”), and the faster pieces astonish, the closing “Vivo” another musical rollercoaster. She’s equally impressive in the demonic “Fanfares” from Ligeti’s first book of Etudes, “a dance with danger, with fire and fireworks”, its rhythm reminiscent of the last of Bartók's Six Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm from Mikrokosmos. I’ve not heard the fourth dance sound quite this jazzy before, and the motoric second is pushed to the limit. This is exhilarating pianism. Hamos is equally persuasive in the earlier 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs, here sounding like improvisations.

Meredith Monk’s short piano piece Ellis Island was composed for her 1981 film of the same name, a repetitive but mellifluous jewel in Hamos’s hands, and her transcription of Charles Mingus’s Myself When I am Real is technically brilliant and wonderfully played. A pity that more contemporary American music wasn’t included, the album concluding unexpectedly but deliciously with Schubert’s D187 Hungarian Melody. Hamos’s very personal booklet essay is an interesting read and the recording has remarkable presence.

O Sacrum Convivium: Music for the Solemnity of Corpus Christi The Choir of Buckfast Abbey/Matthew Searles (Ad Fontes)

O Sacrum Convivium: Music for the Solemnity of Corpus Christi The Choir of Buckfast Abbey/Matthew Searles (Ad Fontes)

Robert Pecksmith’s sleeve note describes the Catholic Solemnity of Corpus Christi as a celebration of both past and the present. So it’s fitting that the repertoire on this album from Matthew Searles’ Buckfast Abbey Choir ranges from Gregorian chant to a contemporary Mass setting first performed in 2024, with individual numbers interspersed with movements from an organ work composed in the 1950s. The mixture works well: I began listening to O Sacrum Convivium on a long drive and was instantly drawn in. Spectacular engineering helps, the abbey’s resonant acoustic aiding the performances rather than impeding them. The “Ante Introitum” from Anton Heiller’s four-movement In festo Corporis Christi is an engaging opener. Heiller was a close friend of Hindemith, and you can hear the older composer’s influence in the clean contrapuntal lines and idiosyncratic use of tonality. Note how the music ends on a unison D, which becomes the starting note for the first snatch of plainsong.

The new commission, Martin Baker’s Missa O sacrum convivium!, is based around a pair of chants, the melodies occasionally quoted literally. Searles’ 29 voice choir sings beautifully, the sound rich and full of impact. Organist Charles Maxtone-Smith draws some warm, mellow sonorities from the Abbey’s Ruffati organ. It’s followed by the Solemn Vespers and Benediction, a highlight being a brief but exquisite setting of the Lord’s Prayer by Rimsky-Korsakov. The service closes with Stanfield’s “Sweet Sacrament Divine”, the organ accompaniment subtly beefed up in Searles’ new arrangement. Documentation is excellent, with full texts and translations, the album snazzily designed and presented as a small hardback book. Recommended.

- Read more Classical reviews ontheartsdesk

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

This year's big anniversary celebrated with a pair of boxes, plus clarinets, pianos and sacred music

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

This year's big anniversary celebrated with a pair of boxes, plus clarinets, pianos and sacred music

BBC Proms: Liu, Philharmonia, Rouvali review - fine-tuned Tchaikovsky epic

Sounds perfectly finessed in a colourful cornucopia

BBC Proms: Liu, Philharmonia, Rouvali review - fine-tuned Tchaikovsky epic

Sounds perfectly finessed in a colourful cornucopia

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: A Mass of Life, BBCSO, Elder review - a subtle guide to Delius's Nietzschean masterpiece

Mark Elder held back from blasting the audience with a wall of sound

BBC Proms: A Mass of Life, BBCSO, Elder review - a subtle guide to Delius's Nietzschean masterpiece

Mark Elder held back from blasting the audience with a wall of sound

BBC Proms: Le Concert Spirituel, Niquet review - super-sized polyphonic rarities

Monumental works don't quite make for monumental sounds in the Royal Albert Hall

BBC Proms: Le Concert Spirituel, Niquet review - super-sized polyphonic rarities

Monumental works don't quite make for monumental sounds in the Royal Albert Hall

Frang, Romaniw, Liverman, LSO, Pappano, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - sunlight, salt spray, Sea Symphony

Full force of the midday sea in the Usher Hall, thanks to the best captain at the helm

Frang, Romaniw, Liverman, LSO, Pappano, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - sunlight, salt spray, Sea Symphony

Full force of the midday sea in the Usher Hall, thanks to the best captain at the helm

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Kolesnikov, Tsoy / Liu, NCPA Orchestra, Chung, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - transfigured playing and heavenly desire

Three star pianists work wonders, and an orchestra dazzles, at least on the surface

Kolesnikov, Tsoy / Liu, NCPA Orchestra, Chung, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - transfigured playing and heavenly desire

Three star pianists work wonders, and an orchestra dazzles, at least on the surface

Add comment