Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help! | reviews, news & interviews

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Do we need any more Beatles books? The answer is: that’s the wrong question. What we need is more Beatles books that are worth reading. As the musician and music historian Bob Stanley pointed out, in his 2007 review of Jonathan Gould’s Can’t Buy Me Love, probably the best biography of The Beatles to date, “the subject is pretty much inexhaustible if the writer is good enough.”

Gould is more than good enough, and he spent nearly two decades writing his book; whereas Ian Leslie has worked his up from a Covid-era blog post paean to Paul McCartney that went, as they say, viral. Leslie attests to Johnathan Gould’s influence in his acknowledgements, as well as recommending a slew of Beatles podcasts, including Diana Erikson’s "One Sweet Dream", a January 2022 episode of which provides much of the thematic ballast for his book.

The trouble is that Leslie has cherry-picked some aspects of that episode – in which Erikson and the wonderful singer-songwriter Aimee Mann had a fascinating, nuanced discussion on Peter Jackson’s Get Back film and what it revealed about the Beatles’ interrelationships – and then chronically over-simplified and absolutized them. In particular, Leslie gloms onto John Lennon’s ironic aside to Paul McCartney – “It’s like you and me are lovers” – and uses this to promote the idea that Lennon and McCartney’s relationship should be seen as a romance, a “love story”.

Ignoring George Harrison and Ringo Starr almost entirely, Leslie fatally mistakes the nature of The Beatles, who were, always and indivisibly, a group. Owning up to this, Leslie says he hopes the disservice he’s done Harrison and Starr “isn’t an egregious one” – as though writing out of their own story two musicians who were integral to the success of the greatest band of all time were a trifling matter, easily excused.

So, Leslie’s book ends up being based upon a double fallacy: he misunderstands The Beatles, and he mischaracterises the nature of Lennon and McCartney’s relationship. Leslie attempts to illustrate his theme by means of highlighting some key songs: “Each chapter is anchored around a song that tells us something about the state of their relationship at the time.” This format quickly falls apart, though, and instead most chapters simply repeat swathes of the familiar story, with a layer of cod psychology slathered on top, like too much cowbell on a demo track.

Leslie sees everything through the lens of his reductive, presumptuous amateur psychoanalysis. There’s scarcely a Beatles song that doesn’t strike him as carrying a subtextual message from Lennon to McCartney or vice versa. His examples run the gamut from screamingly obvious to highly spurious.

His other thematic obsession is with Lennon and McCartney’s respective mother fixations, to the extent that he finds mothers wherever he looks, including "Tell Me Why" and – yes – "Here, There, and Everywhere". (Oddly enough, Leslie does not pursue Aimee Mann’s perceptive comment that, during the end times as showcased in the Get Back film, Paul seems to be almost playing the role of mother to John.)

His other thematic obsession is with Lennon and McCartney’s respective mother fixations, to the extent that he finds mothers wherever he looks, including "Tell Me Why" and – yes – "Here, There, and Everywhere". (Oddly enough, Leslie does not pursue Aimee Mann’s perceptive comment that, during the end times as showcased in the Get Back film, Paul seems to be almost playing the role of mother to John.)

One of Leslie’s more preposterous suggestions is that “there is a plaintive quality to John’s vocal” in "I Want to Hold Your Hand" that “evokes a boy’s need for a mother’s touch”. Unless you want to push very hard indeed on the Oedipal angle, a mother’s touch is surely the last thing that song is concerned with. Somebody needs to sit Leslie down and tell him about the birds and the bees and the meaning of rock and roll.

Conversely, when there are obvious resonances, Leslie sometimes seems oblivious to them. His chapter on "Julia" notes only in passing that Yoko means “Ocean Child”, eliding Lennon’s conflation of "Julia" with Yoko Ono, and the fact that Lennon took to calling Ono “Mother”. Then again, as is often the case, Leslie’s discussion of the titular song is tacked on to the end of the chapter as an afterthought. He spends most of his chapter on "Julia", one of Lennon’s most nakedly autobiographical Beatles songs, talking about Paul and Linda McCartney.

Relentlessly pursuing his psychoanalytical hobbyhorses also leads Leslie to make factual errors. Positing that it was LSD that led Lennon to mine his childhood for subject matter, Leslie adduces "In My Life", "She Said She Said", and "Yellow Submarine" as examples. The first two are arguable, the third one a telling error: "Yellow Submarine" was written by Paul McCartney.

Meanwhile, his chapter on "Martha My Dear" contains a straight lift of a simile used by Aimee Mann in the "One Sweet Dream" podcast: that McCartney, in his fervour for playing music, is like a dog forever wanting a ball to be thrown. Here too, Leslie suggests that Martha, Paul McCartney’s beloved Old English Sheepdog, is a “contender for fifth Beatle”. This would no doubt come as sobering news to, say, George Martin, Brian Epstein, Pete Best, Stuart Sutcliffe, or Billy Preston.

After the Beatles split, the media began to portray John Lennon and Paul McCartney as polar opposites. Lennon was the caustic rebel, an edgy, serious, avant-garde artist, whereas Paul McCartney was seen as a schoolmarmish, middlebrow, middle-of-the-road purveyor of cheesy sentimentality. Lennon’s revisionist, acerbic interviews, while great fun to read, did much to fuel this false narrative, as did the myopic male critics who had hard-ons for Lennon and parroted his often outrageous lies as facts. By the 1980s, when the egregious Philip Norman (who hated The Beatles, their music, their fans, and their decade) published his virulently anti-McCartney biography Shout!, legend had become accepted fact: Lennon was deified as some sort of rock and roll Che Guevara, while poor old Macca was associated with Mull of Kintyre, vegetarian sausages, and thumbs that were forever stuck in "aloft" mode.

But this misleading view of Lennon and McCartney has long been comprehensively debunked. Reality is never that straightforward anyway: John had a fair bit of Paul’s sentimentality, and Paul’s big heart contained a good-sized sliver of Lennon’s iciness. The Yin had plenty of Yang. Leslie acknowledges this, noting that the myth persists only in “moth-eaten form”; yet he still feels he needs to refute it. In doing so, he goes to the other extreme, always giving the edge to McCartney as an artist, presenting him as the stable, mature, reasonable partner forever having to patiently tolerate Lennon’s shortcomings, neuroses, and bad behaviour.

Leslie doesn’t usually write about music. He’s known for what might charitably be termed “popular psychology”, books with titles such as Conflicted: Why Arguments Are Tearing Us Apart and How They Can Bring Us Together. He also writes about politics: one of his hot takes is that Donald Trump isn’t really a racist. Aye right, Ian, and I’m a hippopotamus! Aside from his risible psychoanalysing, and obvious McCartney bias, what also stands out here is the sense the reader gets of The Beatles from Leslie’s book: there’s a slightly fusty feel to it all, as though Leslie’s Beatles are frozen in aspic. This is The Beatles with all the grit sieved out of them. Leslie’s prose is smooth and well-crafted, but curiously simplistic, bordering on prissy. He has a habit of defining quite mundane terms: no doubt he had an eye on the US market when he opted to explain what Desert Island Discs is, but would even an American reader require Leslie’s (slightly inaccurate) explanation that the word “buoyed” means “to keep afloat”?

Towards the end of the book, Leslie spirals off into wild theorising about Lennon and McCartney’s “love story” relationship not being widely acknowledged because “we can’t handle” the idea that two men might have a relationship that “isn’t sexual but is romantic”. Invoking Plato’s Symposium, Michel de Montaigne and Étienne de La Boétie, Leslie claims that Lennon and McCartney “loved each other, that through music they found a way to share this love with everyone in the world”. You’d have to have a heart of stone not to laugh.

In his acknowledgements, Leslie thanks “all previous Beatles authors for not getting there before me.” In pop-cultural terms, this statement is the equivalent of claiming that you discovered the Double Helix this morning, whilst having your Rice Krispies. The personal and creative relationships between Lennon and McCartney are at the heart of practically every Beatles book ever written, and their artistic partnership is surely the most scrutinised in human history. The only new element here is Leslie’s cockamamie notion that we should view the story of The Beatles as a love affair between John and Paul. Ultimately, Leslie’s book is a travesty which does as much of a disservice to The Beatles as anything Philip Norman or Albert Goldman ever managed. The Beatles deserve better than this, as do their fans.

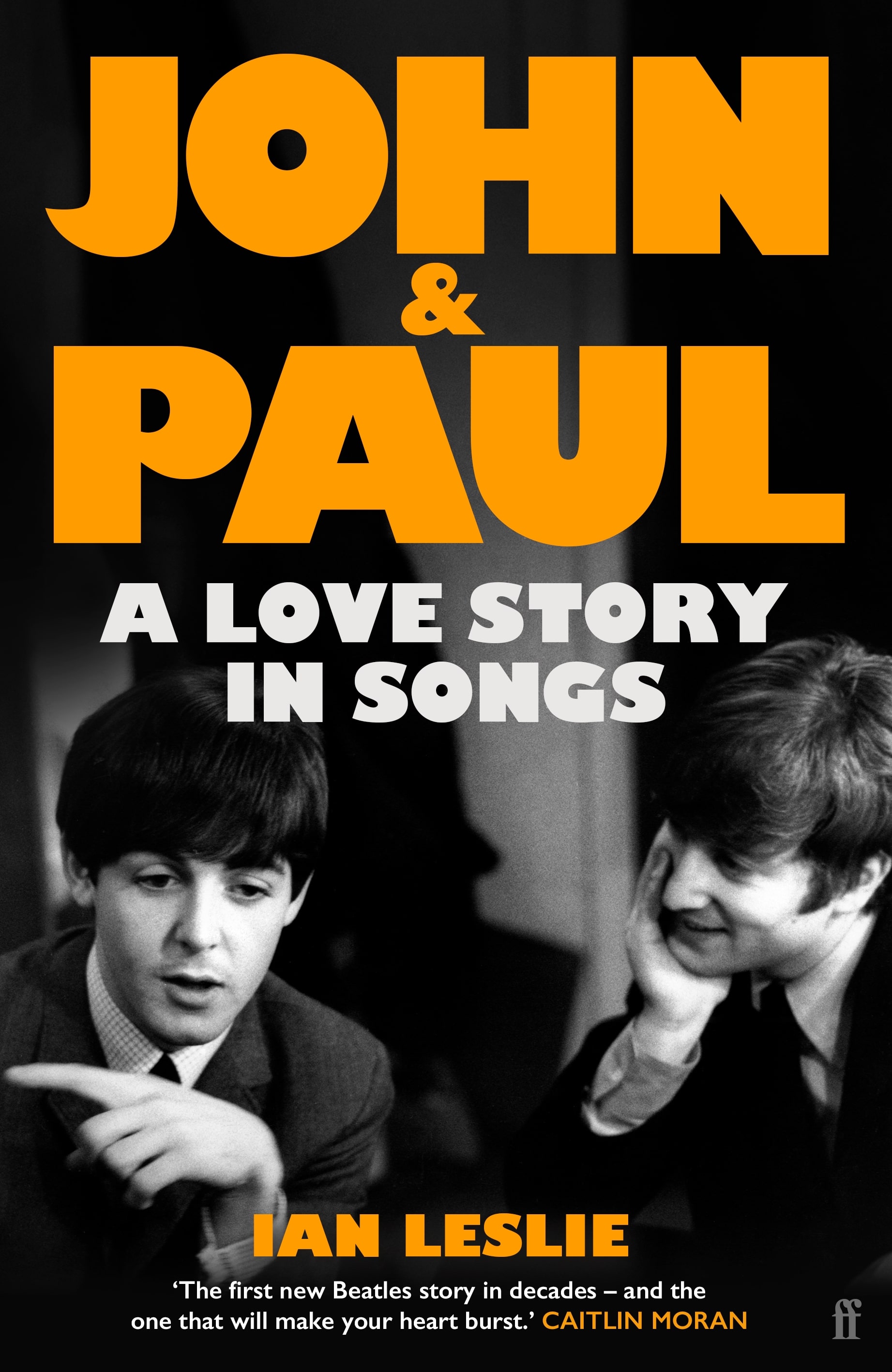

- John and Paul: A Love Story in Songs (Faber & Faber, £25)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

What a churlish and childish

What a churlish and childish review of Ian Leslie's excellent and very readable book.

Terrible review undermined by

Terrible review undermined by the writer's own lack of knowledge. It's been established that no, actually, Yellow Submarine was NOT "written by McCartney." Also, the weird baseless political assertion "Trump us a racist!" only tells us this clown doesn't live in a world of facts and feels compelled to signal to his fellow phonies who repeat things without critical thought or evidence to support them. Ergo, can't take his review seriously when all it amounts to is "This book doesn't align with my beliefs even though I have nothing to support my beliefs."